This term has other meanings, see Babushkin.

| City Babushkin Coat of arms |

| A country | Russia, Russia |

| Subject of the federation | BuryatiaBuryatia |

| Municipal district | Kabansky |

| urban settlement | "Babushkinskoe" |

| Coordinates | 51°43′00″ n. w. 105°52′00″ E. long / 51.71667° north w. 105.86667° E. d. / 51.71667; 105.86667 (G) [www.openstreetmap.org/?mlat=51.71667&mlon=105.86667&zoom=11 (O)] (Z)Coordinates: 51°43′00″ N. w. 105°52′00″ E. long / 51.71667° north w. 105.86667° E. d. / 51.71667; 105.86667 (G) [www.openstreetmap.org/?mlat=51.71667&mlon=105.86667&zoom=11 (O)] (I) |

| Based | in 1760 |

| Former names | until 1892 — Mysovsky settlement until 1902 - |

| City with | 1902 |

| Center height | 470 |

| Climate type | sharply continental |

| Population | ↘4623[1] people (2016) |

| National composition | Russians, Buryats and others |

| Confessional composition | Orthodox, Buddhists and others |

| Names of residents | babushkinets, babushkinets[2] |

| Timezone | UTC+8 |

| Telephone code | +7 30138 |

| Postcode | 671230 |

| Vehicle code | 03 |

| OKATO code | [classif.spb.ru/classificators/view/okt.php?st=A&kr=1&kod=81224503000 81 224 503 000] |

| Babushkin Moscow |

| Ulan-Ude Kabansk Babushkin |

Audio, photo and video

on Wikimedia Commons

K: Settlements founded in 1760

Babushkin

(until 1941 -

Mysovsk

) - a city in the Kabansky district of the Republic of Buryatia. Administrative center of the urban settlement "Babushkinskoye". Population - 4623[1] people. (2016).

One of the five historical cities of Buryatia. In the city there is the Mysovaya railway station on the Trans-Siberian Railway.

Climate

Thanks to its location on the shores of Lake Baikal, winters are relatively mild here (compared to Irkutsk or Ulan-Ude). Temperatures in winter range on average from −5 °C to −25 °C. Summers are cool, with high rainfall. Average temperatures: +15 °C to +25 °C. Autumn is, on average, warmer than spring.

| Average daily air temperature and precipitation[3] | |||||||||||||

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | But I | Dec | Year |

| Average temperature, °C | −14,5 | −15,8 | −8,6 | −0,5 | 6,3 | 10,7 | 14,4 | 14,4 | 8,9 | 2,7 | −4,0 | −7,9 | 0,6 |

| Precipitation, mm | 19,2 | 10,5 | 13,9 | 23,5 | 42,9 | 79,1 | 108,9 | 101,6 | 67,6 | 33,4 | 32,9 | 37,7 | 576 |

Story

The settlement of the Mysovsky Posolsky Monastery on the site of the current city was allegedly founded between 1760 and 1765. Here began the Udunga highway through Khamar-Daban, built by Kyakhta merchants to transport goods from China. They also built a pier on Lake Baikal. Along the Krugomorsky tract through Mysovaya convicts were sent to Nerchinsk and Akatuy.

In 1892, a postal station was founded near the Mysovsky settlement and the local merchants began to petition for the settlement to be given the status of a city.

In 1900, the Mysovaya railway station was founded. Before the construction of the Circum-Baikal Railway, the Mysovaya pier received ferries with trains from the western shore of Lake Baikal.

On May 31, 1902, by the highest command, the village at Mysovoy station received the status of a district-free city in the Trans-Baikal region and the official name - Mysovsk

[4].

During the Russian-Japanese War, the Smolensk Red Cross infirmary with 200 beds operated in the city[5].

During the revolution of 1905-1907, Mysovsk was one of the centers of the revolutionary movement in Transbaikalia. On January 18, 1906, six revolutionaries, including I.V. Babushkin, were shot here by the punitive forces of General Meller-Zakomelsky.

In January 1914, a congress of cooperators of western Transbaikalia was held in Verkhneudinsk, at which the Pribaikalsky Trade and Industrial Partnership of Cooperatives “Pribaikalsoyuz” was created. After this, cooperative consumer societies “Economy” arose in the cities of Troitskosavsk, Mysovsk, Barguzin[6].

In 1917, the Mysovsky Assumption Monastery for women was created from the Orthodox community[7].

In August 1918, the station and the city were captured by the White Czechs. During the Civil War, Mysovsk was occupied by the Americans, Japanese, Ungernovites, Semyonovites, and Kappelevites. On February 11, 1920, in Mysovsk, General S. N. Voitsekhovsky established by his order one of the highest awards of the White movement in eastern Russia - the badge “For the Great Siberian Campaign.”

Until 1927, the city was part of the Irkutsk district of the Irkutsk province. On June 6, 1925, the city was transformed into a workers' settlement. On March 15, 1927, Mysovsk became part of the Buryat-Mongolian Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic, and from September of the same year - into the newly formed Kabansky district of the BM Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic.

In 1931, the shipyard of the East Siberian Fishing Trust began operating in Mysovsk[8].

On January 18, 1941, by Decree of the Presidium of the Supreme Soviet of the RSFSR, Mysovsk again acquired the status of a city (already of republican subordination) and was renamed Babushkin

[9], in honor of the professional revolutionary I.V. Babushkin, who was shot at Mysovaya station in 1906.

In 1959, the city of Babushkin lost its status as a city of republican subordination.

On January 13, 1965, the city of Babushkin, the towns of Vydrino, Selenginsk, Kamensk and Tankhoi, as well as the Posolsky Village Council were transferred from the Pribaikalsky district to the Kabansky district[10].

Famous people

Rokossovsky and Mysovsk

Konstantin Konstantinovich Rokossovsky was treated in a hospital in Mysovsk . From the memoirs of K.K. Rokossovsky (military memoirs “A Soldier’s Duty”): “In June 1921, the Red Army finished off Baron Ungern on the border with Mongolia. At the village of Zhelturinskaya, the 35th Cavalry Regiment, which I commanded, attacked the Ungernov cavalry that had broken through our infantry. In this battle I was wounded for the second time, in the leg with a broken bone.” For his distinction in the battle on June 2, 1921 near the village of Zhelturinskaya, K. K. Rokossovsky was awarded the second Order of the Red Banner. When, at the end of July 1921, Mysovsk was under the threat of an attack by Ungern, the untreated 24-year-old Rokossovsky (medics, at his request, bandaged his sore leg to two sticks) formed a combined detachment of 700 fighters and set out to meet the enemy.

Notes

- ↑ 123

www.gks.ru/free_doc/doc_2016/bul_dr/mun_obr2016.rar Population of the Russian Federation by municipalities as of January 1, 2016 - Gorodetskaya I. L., Levashov E. A.

[books.google.com/books?id=Do8dAQAAMAAJ&dq=%D0%91%D0%B0%D0%B1%D1%83%D1%88%D0%BA%D0 %B8%D0%BD Babushkin] // Russian names of residents: Dictionary-reference book. - M.: AST, 2003. - P. 37. - 363 p. — 5000 copies. — ISBN 5-17-016914-0. - [www.worldclimate.com/cgi-bin/grid.pl?gr=N51E105 World Climate]

- Correspondence // Eastern Review. No. 34, February 10, 1904, p.3.

- E.V. Pavlov

In the Far East in 1905: From observations during the war with Japan / Life surgeon E. Pavlov. — St. Petersburg: book printer. Schmidt, 1907. appendix p.56 - Basaev G. D., Khutashkeeva S. D.

Cooperative movement in Western Transbaikalia on the eve and during the First World War // Humanitarian vector. Series: History, political science. 2012. No. 2. P.105-109. - E. V. Drobotushenko

Economic activity of Orthodox monasteries of the Transbaikal diocese in the second half of the 19th - early 20th centuries // Humanitarian vector. Series: Pedagogy, psychology. 2008. No. 2. P.86-95. - V. Semenov

Strangers are operating at the shipyard // Buryat-Mongolskaya Pravda, No. 44 (5522), February 22, 1935, p.4 - Buryat-Mongolskaya Pravda, No. 18 (7251), January 22, 1941, p. 1.

- [burstat.gks.ru/wps/wcm/connect/rosstat_ts/burstat/resources/a866c400476c15d4bf74ff1e21662943/number+of population.xls Population of the Republic of Buryatia by district (error 50 people)]. Retrieved February 25, 2015. [www.webcitation.org/6WbgRIn32 Archived from the original on February 25, 2015].

- ↑ 1234567891011

[www.mojgorod.ru/r_burjatija/babushkin/ People's encyclopedia “My City”. Babushkin]. Retrieved October 12, 2013. [www.webcitation.org/6KJpszQ41 Archived from the original on October 12, 2013]. - [demoscope.ru/weekly/ssp/rus59_reg2.php All-Union Population Census of 1959. The size of the urban population of the RSFSR, its territorial units, urban settlements and urban areas by gender] (Russian). Demoscope Weekly. Retrieved September 25, 2013. [www.webcitation.org/6GDOghWC9 Archived from the original on April 28, 2013].

- [demoscope.ru/weekly/ssp/rus70_reg2.php All-Union Population Census of 1970 The size of the urban population of the RSFSR, its territorial units, urban settlements and urban areas by gender.] (Russian). Demoscope Weekly. Retrieved September 25, 2013. [www.webcitation.org/6GDOiMstp Archived from the original on April 28, 2013].

- [demoscope.ru/weekly/ssp/rus79_reg2.php All-Union Population Census of 1979 The size of the urban population of the RSFSR, its territorial units, urban settlements and urban areas by gender.] (Russian). Demoscope Weekly. Retrieved September 25, 2013. [www.webcitation.org/6GDOjhZ5L Archived from the original on April 28, 2013].

- [demoscope.ru/weekly/ssp/rus89_reg2.php All-Union Population Census of 1989. Urban population]. [www.webcitation.org/617x0o0Pa Archived from the original on August 22, 2011].

- [www.gks.ru/bgd/regl/B09_109/IssWWW.exe/Stg/d01/tabl-21-09.xls Number of permanent population of the Russian Federation by cities, urban-type settlements and districts as of January 1, 2009]. Retrieved January 2, 2014. [www.webcitation.org/6MJmu0z1u Archived from the original on January 2, 2014].

- [www.gks.ru/free_doc/new_site/perepis2010/itogi/tom1/pub-01-05.xls Results of the 2010 All-Russian Population Census. 5. Population of Russia, federal districts, constituent entities of the Russian Federation, districts, urban settlements, rural settlements - district centers and rural settlements with a population of 3 thousand people or more]. Retrieved November 14, 2013. [www.webcitation.org/6L7PRbEbU Archived from the original on November 14, 2013].

- ↑ 12

[burstat.gks.ru/wps/wcm/connect/rosstat_ts/burstat/resources/d537ed8043fb0d72ad80efd92111eac8/Population+on+1+January.xlsx Buryatia. Population as of January 1, 2011-2014]. Retrieved June 18, 2014. [www.webcitation.org6QQKedzoB/ Archived from the original on June 18, 2014]. - [www.gks.ru/free_doc/doc_2012/bul_dr/mun_obr2012.rar Population of the Russian Federation by municipalities. Table 35. Estimated resident population as of January 1, 2012]. Retrieved May 31, 2014. [www.webcitation.org/6PyOWbdMc Archived from the original on May 31, 2014].

- [www.gks.ru/free_doc/doc_2013/bul_dr/mun_obr2013.rar Population of the Russian Federation by municipalities as of January 1, 2013. - M.: Federal State Statistics Service Rosstat, 2013. - 528 p. (Table 33. Population of urban districts, municipal districts, urban and rural settlements, urban settlements, rural settlements)]. Retrieved November 16, 2013. [www.webcitation.org/6LAdCWSxH Archived from the original on November 16, 2013].

- [www.gks.ru/free_doc/doc_2015/bul_dr/mun_obr2015.rar Population of the Russian Federation by municipalities as of January 1, 2015]. Retrieved August 6, 2015. [www.webcitation.org/6aaNzOlFO Archived from the original on August 6, 2015].

- [www.gks.ru/free_doc/doc_2014/bul_dr/mun_obr2014.rar Population of the Russian Federation by municipalities as of January 1, 2014]. Retrieved August 2, 2014. [www.webcitation.org/6RWqP50QK Archived from the original on August 2, 2014].

- [www.museum.ru/M1201 Museum of I.V. Babushkin on museum.ru]

Excerpt characterizing Babushkin (Buryatia)

“Yes,” Pierre answered with his now familiar smile of gentle mockery. “They even tell me about such miracles as I have never seen in my dreams.” Marya Abramovna invited me to her place and kept telling me what had happened to me, or was about to happen. Stepan Stepanych also taught me how to tell things. In general, I noticed that it is very peaceful to be an interesting person (I am an interesting person now); they call me and they tell me. Natasha smiled and wanted to say something. “We were told,” Princess Marya interrupted her, “that you lost two million in Moscow.” Is this true? “And I became three times richer,” said Pierre. Pierre, despite the fact that his wife’s debts and the need for buildings changed his affairs, continued to say that he had become three times richer. “What I have undoubtedly won,” he said, “is freedom...” he began seriously; but decided against continuing, noticing that this was too selfish a subject of conversation. -Are you building? - Yes, Savelich orders. – Tell me, did you not know about the death of the Countess when you stayed in Moscow? - said Princess Marya and immediately blushed, noticing that by making this question after his words that he was free, she ascribed to his words a meaning that they, perhaps, did not have. “No,” answered Pierre, obviously not finding the interpretation that Princess Marya gave to his mention of her freedom awkward. “I learned this in Orel, and you can’t imagine how it struck me.” We were not exemplary spouses,” he said quickly, looking at Natasha and noticing in her face the curiosity about how he would respond to his wife. “But this death struck me terribly.” When two people quarrel, both are always to blame. And one’s own guilt suddenly becomes terribly heavy in front of a person who no longer exists. And then such death... without friends, without consolation. “I’m very, very sorry for her,” he finished and was pleased to notice the joyful approval on Natasha’s face. “Yes, here you are again, a bachelor and a groom,” said Princess Marya. Pierre suddenly blushed crimson and tried for a long time not to look at Natasha. When he decided to look at her, her face was cold, stern and even contemptuous, as it seemed to him. – But did you really see and talk with Napoleon, as we were told? - said Princess Marya. Pierre laughed. - Never, never. It always seems to everyone that being a prisoner means being a guest of Napoleon. Not only have I not seen him, but I have also not heard of him. I was in much worse company. Dinner ended, and Pierre, who at first refused to talk about his captivity, gradually became involved in this story. - But is it true that you stayed to kill Napoleon? – Natasha asked him, smiling slightly. “I guessed it when we met you at the Sukharev Tower; remember? Pierre admitted that this was the truth, and from this question, gradually guided by the questions of Princess Marya and especially Natasha, he became involved in a detailed story about his adventures. At first he spoke with that mocking, meek look that he now had at people and especially at himself; but then, when he came to the story of the horrors and suffering that he had seen, he, without noticing it, became carried away and began to speak with the restrained excitement of a person experiencing strong impressions in his memory. Princess Marya looked at Pierre and Natasha with a gentle smile. In this whole story she saw only Pierre and his kindness. Natasha, leaning on her arm, with a constantly changing expression on her face, along with the story, watched, without looking away for a minute, Pierre, apparently experiencing with him what he was telling. Not only her look, but the exclamations and short questions she made showed Pierre that from what he was telling, she understood exactly what he wanted to convey. It was clear that she understood not only what he was saying, but also what he would like and could not express in words. Pierre told about his episode with a child and a woman, for whose protection he was taken, in the following way: “It was a terrible sight, children were abandoned, some were on fire... In front of me they pulled out a child... women, from whom they pulled things off, tore out earrings... Pierre blushed and hesitated. “Then a patrol arrived, and all those who were not robbed, all the men were taken away. And me. – You probably don’t tell everything; “You must have done something…” Natasha said and paused, “good.” Pierre continued to talk further. When he talked about the execution, he wanted to avoid the terrible details; but Natasha demanded that he not miss anything. Pierre started to talk about Karataev (he had already gotten up from the table and was walking around, Natasha was watching him with her eyes) and stopped. - No, you cannot understand what I learned from this illiterate man - a fool. “No, no, speak up,” said Natasha. - Where is he? “He was killed almost in front of me.” - And Pierre began to tell the last time of their retreat, Karataev’s illness (his voice trembled incessantly) and his death. Pierre told his adventures as he had never told them to anyone before, as he had never recalled them to himself. He now saw, as it were, a new meaning in everything that he had experienced. Now, when he was telling all this to Natasha, he was experiencing that rare pleasure that women give when listening to a man - not smart women who, while listening, try to either remember what they are told in order to enrich their minds and, on occasion, retell it or adapt what is being told to your own and quickly communicate your clever speeches, developed in your small mental economy; but the pleasure that real women give, gifted with the ability to select and absorb into themselves all the best that exists in the manifestations of a man. Natasha, without knowing it herself, was all attention: she did not miss a word, a hesitation in her voice, a glance, a twitch of a facial muscle, or a gesture from Pierre. She caught the unspoken word on the fly and brought it directly into her open heart, guessing the secret meaning of all Pierre’s spiritual work. Princess Marya understood the story, sympathized with it, but now she saw something else that absorbed all her attention; she saw the possibility of love and happiness between Natasha and Pierre. And for the first time this thought came to her, filling her soul with joy. It was three o'clock in the morning. Waiters with sad and stern faces came to change the candles, but no one noticed them. Pierre finished his story. Natasha, with sparkling, animated eyes, continued to look persistently and attentively at Pierre, as if wanting to understand something else that he might not have expressed. Pierre, in bashful and happy embarrassment, occasionally glanced at her and thought of what to say now in order to shift the conversation to another subject. Princess Marya was silent. It didn’t occur to anyone that it was three o’clock in the morning and that it was time to sleep. “They say: misfortune, suffering,” said Pierre. - Yes, if they told me now, this minute: do you want to remain what you were before captivity, or go through all this first? For God's sake, once again captivity and horse meat. We think how we will be thrown out of our usual path, that everything is lost; and here something new and good is just beginning. As long as there is life, there is happiness. There is a lot, a lot ahead. “I’m telling you this,” he said, turning to Natasha. “Yes, yes,” she said, answering something completely different, “and I would like nothing more than to go through everything all over again.” Pierre looked at her carefully. “Yes, and nothing more,” Natasha confirmed. “It’s not true, it’s not true,” Pierre shouted. – It’s not my fault that I’m alive and want to live; and you too. Suddenly Natasha dropped her head into her hands and began to cry. - What are you doing, Natasha? - said Princess Marya. - Nothing, nothing. “She smiled through her tears at Pierre. - Goodbye, time to sleep. Pierre stood up and said goodbye. Princess Marya and Natasha, as always, met in the bedroom. They talked about what Pierre had told. Princess Marya did not speak her opinion about Pierre. Natasha didn't talk about him either. “Well, goodbye, Marie,” Natasha said. – You know, I’m often afraid that we don’t talk about him (Prince Andrei), as if we are afraid to humiliate our feelings and forget. Princess Marya sighed heavily and with this sigh acknowledged the truth of Natasha’s words; but in words she did not agree with her. - Is it possible to forget? - she said. “It felt so good to tell everything today; and hard, and painful, and good. “Very good,” said Natasha, “I’m sure he really loved him.” That's why I told him... nothing, what did I tell him? – suddenly blushing, she asked. - Pierre? Oh no! How wonderful he is,” said Princess Marya. “You know, Marie,” Natasha suddenly said with a playful smile that Princess Marya had not seen on her face for a long time. - He became somehow clean, smooth, fresh; definitely from the bathhouse, do you understand? - morally from the bathhouse. Is it true? “Yes,” said Princess Marya, “he won a lot.” - And a short frock coat, and cropped hair; definitely, well, definitely from the bathhouse... dad, it used to be... “I understand that he (Prince Andrei) did not love anyone as much as he did,” said Princess Marya. – Yes, and it’s special from him. They say that men are friends only when they are very special. It must be true. Is it true that he doesn't resemble him at all? - Yes, and wonderful. “Well, goodbye,” Natasha answered. And the same playful smile, as if forgotten, remained on her face for a long time. Pierre could not fall asleep for a long time that day; He walked back and forth around the room, now frowning, pondering something difficult, suddenly shrugging his shoulders and shuddering, now smiling happily. He thought about Prince Andrei, about Natasha, about their love, and was either jealous of her past, then reproached her, then forgave himself for it. It was already six o'clock in the morning, and he was still walking around the room. “Well, what can we do? If you can’t do without it! What to do! So, this is how it should be,” he said to himself and, hastily undressed, went to bed, happy and excited, but without doubts and indecisions. “We must, strange as it may be, no matter how impossible this happiness is, we must do everything in order to be husband and wife with her,” he said to himself. Pierre, a few days before, had set Friday as the day of his departure for St. Petersburg. When he woke up on Thursday, Savelich came to him for orders about packing his things for the road. “How about St. Petersburg? What is St. Petersburg? Who's in St. Petersburg? – he asked involuntarily, although to himself. “Yes, something like that a long, long time ago, even before this happened, I was planning to go to St. Petersburg for some reason,” he remembered. - From what? I'll go, maybe. How kind and attentive he is, how he remembers everything! - he thought, looking at Savelich’s old face. “And what a pleasant smile!” - he thought.

The Buryat branch of the Russian Geographical Society, within the framework of the grant from the Russian Geographical Society "Udunginsky Merchant Tract", plans to study and popularize the history of the Buryat section of the Tea Route - the Udunginsky Merchant Tract, describe its current state and develop a tourist route of the same name. Our material is about the significance of this route.

We were looking for a short and accessible route

The tea caravan route between Asia and Europe crossed the territory of present-day Mongolia and went through Russia to Europe. Its length from Beijing to Moscow alone was approximately 9,000 km, and in terms of trade volume it was only slightly inferior to the traditional Silk Road routes that ran through Central Asia and the Middle East.

The “Russian Tea Road” began in the city of Wuhan and was divided into several land and water routes that passed through more than 150 cities in three countries. A general line can be drawn from Wuhan to Beijing, then to Hohhot, Urga (now Ulaanbaatar), Darkhan, Troitskosavsk (now Kyakhta). Kyakhta was once the main trading center of the Tea Route; it was not for nothing that it was called the “Russian capital of tea.” From Kyakhta the route went to Verkhneudinsk (now Ulan-Ude) and further to Krasnoyarsk, Nizhny Novgorod, Moscow and St. Petersburg. From Moscow, radial routes went to the south, north and west of the country. Since the advent of the Tea Road, Kyakhta merchants have been looking for more convenient and shorter roads from China to Moscow and St. Petersburg, as well as the most important fairs of Nizhny Novgorod and Irbit. The water route to Irkutsk along the winding Selenga River in winter was extremely long, and for a long time they used the Dzhida tract to reach Irkutsk, through the Naryn machine tool, the peaks of the Temnik and Snezhnaya rivers, and the KhamarDaban ridge, which led to the Kultuk station. This route from the village of Kopcheranka was carried out in pack. Later from r. Snezhnaya to Lake Baikal, a new direction was found through Nuken-Daban, leading to the Murino railway station. This path was built by the Ust-Kyakhta merchant Igumnov and was called the Igumnovsky (started in 1835, completed in 1839) tract. Just like along the road to Kultuk, cargo was transported along this road by pack method on horseback and only in winter. Both of these paths require crossing the Khamar-Daban ridge in its most inaccessible part.

Since the second half of the 19th century. Research was carried out to find shorter and more convenient routes. Thus, the survey of the route to Baikal from Selenginsk in July 1881 was carried out by Captain Efimy Semenovich Putilov, and in September the centurion Igumnov walked along the same direction. The Kyakhta merchants were extremely interested in the route to Lake Baikal with the easiest passes and, if possible, accessible to wheeled traffic. In 1884, this path was drawn and named the Udunginsky tract.

The initial part of the route Mysovaya - Kyakhta, for the first 50 versts, coincided with the beginning of the Dzhidinsky tract, travel along which became especially lively in connection with the discovery of gold mines in the upper reaches of the river. Jids at the end of the 19th century. The distance from Verkhneudinsk to Kyakhta along the postal route was 214 versts and from Verkhneudinsk to Mysovaya - 134 versts, the distance from Kyakhta to Mysovaya along the merchant tract - 190 versts.

At this distance, 7 stations were built, not counting the final points (Kyakhta and Mysovaya). Kyakhta merchants spared no expense in improving the route, so the route was furnished with station buildings, bridges, wooden pipes that drained water, and permanent sets of horses and carts with supplies of hay and oats. The merchants spent from 6194 rubles on improvement of the path to Baikal. 14 kopecks up to 11488 rub. 37 kopecks

Uspensky and the travel notebook

In the archives of the Kyakhtinsky Museum of Local Lore. ak. V.A. Obruchev, we found and digitized the manuscript of S.A. Uspensky “The Old Merchant Highway Mysovaya - Kyakhta” circa 1928, an excerpt from which we present verbatim (Spelling and style of the original have been preserved. - Ed.): “For more than 20 years, tea has not been transported along the indicated path and this path is not supported by anyone , so I had to travel that route last summer. I will try to imagine this path before your eyes using my travel notebook.

...The path from Troitskosavsk to Ust-Kyakhta goes (along Laptev) through the dry steppe, passes through the Burgutuysky ridge in the Chuochi area. At half the distance the road approaches the source of the river. Sava, on which the village of Ust-Kyakhta itself is located. The named section of the path is the old historical path to Troitskosavsk, it was followed to the city on the 20th of February 1820 by the famous Speransky, halfway to Ust-Kyakhta I had to see the date 1830 engraved on a stone, a hundred years ago this path was full of excitement. At this time, this direction of the route gives way to a highway laid through the so-called. Vorovskaya Pad, here previously there was only freight traffic, and even then not constantly. From Troitskosavsk to Ust-Kyakhta, as is known, 23 ½ ver. and from Troitskosavsk to Kyakhta. Further on from Ust-Kyakhta the road goes along the right bank of the Selenga. The Selenga here is divided into branches, separating channels and old rivers from itself, encircling with them a number of islands that are flooded into deep water. The road at one time goes along the narrow rocky bank of the old river bed (there is a cave here), and at the 10th verst it comes to the crossing of the Selenga. This crossing was previously located opposite the village. Zarubina, at the 7th verst from Ust-Kyakhta, due to the islands formed here, it was moved 3 versts lower. The crossing is carried out on a carbaz, using oars. There is no permanent transportation here, and yet this crossing connects the vast Dzhidinsky region with our city, in addition, at the time of our passage through the Selenga, the transportation was removed, in the area of Makhai connecting the border population of the villages of TsaganUsuna, Botsiya and Enkhora with the city, so citizens and from these villages, on their way to the city, they used the Zarubinsky transport. The imperfection of the crossing connecting the left bank of the Selenga with the city should have long ago attracted the attention of the administration and measures to improve it.

Next, the path for 7 miles runs along a flat meadow to the river. Jide. Through the river Jidu has a wonderful rope crossing. During rains, the waters of the Jida quickly arrive and therefore this transportation is operational during low water levels; during floods, the carbaz is removed from the rope and the crossing is made by oars. In the past, the crossing of Dzhida was carried out via a bridge. The bridge was built by the Kyakhta merchant N.L. Molchanov to improve traffic to his own mine at the top of the river. Dzhidy, the cost of the bridge at one time was more than 40,000 rubles, about 20 years ago it burned down from careless handling of fire. Just 15 years ago there was only half of the bridge covered; currently there are only 6 abutments left on the water. After crossing Jida, the path goes along the left bank of the river, bordered by the ridge of the Borgoi Mountains, through an area bearing the Mongolian name “Doryaun”. In geography, the steppes are also called “chiev”; on this plain, 5 versts from the river crossing, the Deristuisky datsan is located. From the datsan in the past, the road went into the Ikhirit pad and after a pass through the high Ikhirit ridge it went to the Shabartuy station in the Borgoy steppe; later a version of the road was adopted that was somewhat more distant compared to the Ikhirit one, but without passes, along the vast Borgoy steppe. Not far from the datsan, the path goes along the bank of the picturesque channel of the river. Dzhida, bordered by a ridge of elm trees at the foot of steep mountains. From the road you can see the cliffs where the Dzhida flows here, breaking out of the mountains, the so-called “Cheeks”. The path passed along a rocky plain and 7 versts from the mentioned datsan, directly opposite the “Cheeks”, the Novo-Dzhidinskaya station was previously built. It has not survived to this day. A few steps from the road, traces of a foundation and a pile of bricks are visible, indicating the presence of a furnace here, where the buildings were removed; the local population could not give me information. From Ust-Kyakhta to NovoDzhidinskaya station 28 ½ versts.

Beyond the Novo-Dzhidinskaya station the road opens onto the open steppe “Tsagan-Khutul”. The road follows it for 10 versts in a westerly direction, along the highway to the upper reaches of the Dzhida, and then steeply, almost at a right angle, deviates to the north, cutting through the Borgoy steppe in a northern direction, bypassing the passes through the Borgoy ridge on the eastern side. The Borgoy steppe is a vast basin bordered on all sides by mountains. A small river flows from north to south across the steppe. Borgoi, in the south of the steppe there is a number of salt lakes, into one of which this river flows. The Borgoy steppe is cereal and famous for its fodder. Borgoy oil, meat, especially lamb, is the best in Transbaikalia. Currently, government measures are being taken here to improve sheep breeding and a number of buildings, so-called sheepfolds, are being erected, scattered throughout the southern part of the said steppe. At the 30th verst of the route from Novo-Dzhidinskaya station there was NovoBorgoyskaya station, it is located in the Shabartuy area. Traces of the station are still visible a few steps to the right of the road.

From the former Novo-Borgoi station the area rises; this hill closes the steppe on the northern side. As you rise in the north, the Khamar-Dabana mountains, covered with dense forests, appear, which are cut here by the river. The temnik divides Khamar-Daban into two parts - Big Khamar-Daban on the left bank and Small on the right. Descending from the mentioned hill, the road passes through the small Russian village (Namzyk) Novo-Dmitrievskoye. It was formed from an inn that once stood on a merchant's route and is marked under this name even on geographical maps. Here the Iro River flows along the highway, along which the Iroi Datsan is located. The datsan buildings remain to the left of the road, three miles away, in the upper reaches of the river. Iro is located Irinskie waters, which attract the local Buryat population with their healing qualities. To the right of the tract there remains a prominent economic institution, an agricultural base, and even further to the left of the tract there remains the river valley. Urma, where there are also famous waters, and the road approaches the river. Temnik. But for another three miles the road stretches along the coast. Cliffs and rocks fall into the water from both banks, and only the edge of the bank provides space for the road surface. There is a bridge to cross the river. The bridge is wooden, built by merchants on abutments filled with beautiful graphite-porphyry, red-wax high cliffs made of it approach the river in this place, the length of the bridge is 40 fathoms. During the offensive of Baron Ungern (1921) it was destroyed, but was corrected by the Udungin society. Due to the flood that occurred in June 1927, a small part of it adjacent to the right bank was washed away, and the river was crossed by a ford. Only the two links closest to the right bank of the bridge are damaged, the distance between the second and third spans is filled with longitudinal cramps, and a plank has been laid from the abutments of the second span to the shore. Using stones and boards it was possible to jump to the beginning of the bridge, the rest of which was in fairly satisfactory condition, and thus cross the bridge to the other side of the river. At the crossing, near the bridge, there was the fourth station of the merchant tract Temninskaya. The foundations of the buildings and the remains of the furnaces are visible to this day; the buildings themselves were acquired by the mentioned agricultural base, located 5 versts from the river. Temnik. On this part of the path, the grassy steppe turns into forests, abundantly covering the spurs of Khamar-Daban, among which the mountain [inaudible] rises directly above the river. From Novo-Borgoyskaya station to Temnik is 24 versts.

From Temnik station the tract goes along the river valley. Udungi, along this river and the tract itself is often called Udunginsky. The valley is not wide, but both sides are bordered by mountains. The banks of the river are covered with birch and shrubs; tall, shaggy spruces stand out beautifully among the trees. The roadbed stretches along the left side of the valley. At the beginning of this part of the path, here and there there are scattered yurts of the Udungin population; as you move forward, the valley narrows, the mountains at the beginning of the valley are treeless, now covered with dense, abundant forests. At the 8th verst from Temnik you pass by the Udungin school, even further, at approximately the 20th verst from Temnik the road crosses the river. Udung along a long wooden, fairly well-maintained bridge. R. Udunga slopes towards the east, while the tract goes along the valley of the Khasurta River. The bluish waters of Udunga, bordered by impenetrable thickets near the bridge, make an indelible impression. Ver. Udunginskaya station was located 3 minutes from the bridge. The cramped corner where she stood was visible from the inn to passers-by. From Temnik station to Udunga station it is 23 versts.

From Udunga station the road goes along the river valley. Hasurta. The valley is narrow and surrounded by high cliffs. The narrow left bank of the river remains for the road surface. On this section of the route, the embankment that was placed on the roadbed in the past has been largely demolished by rains and floods, and huge stones have been exposed, making movement extremely difficult. Along the Udunga valley to the Udunginskaya station you always come across yurts of the Buryat population, but from the Udunginskaya station to Mysovaya itself there are no settlements. Huge mountains rise on both sides of the road, the taiga envelops the mountains in all its integrity, this is the route to the former Gudzhirskaya station. At this point the mountains retreat somewhat from the river and traces of the former are clearly visible to the right of the road. Station buildings, on the same road there is a house, just like at the Udunge station, playing the role of an inn. In the past, when there was no wheeled road here, only squirrel and sable hunters reached Gutirka; beyond this place there were no roads to the Khamar-Daban ridge. From Udunga station to Gudzhirskaya 17 versts.

From Gudzhirskaya station the highway goes through the taiga. The mountains that rose on both sides of the tract seem to be lowering, indicating that the tract, rising uphill from Temnik station, is only now approaching the top of the pass through Khamar-Daban. Two miles from the Gudzhir station there used to be a government trading post for buying furs; due to some accident it burned down, and now this is evidenced by the burnt part of the forest. The tract, bordered on both sides by mountains, now leads to the edges, a few steps from which steep slopes began, completely covered with dense forest. 20 versts from the Gudzhir station the road approaches the top of the river [inaudible], which flows into Baikal. Here is a small shelter, the owner of which, K. Parfelov, makes meteorological observations at this interesting point. According to stories, the entire territory of this area was covered with cedar, but about 40 years ago a forest fire destroyed these forests, and aspen and birch grew in their place. After [inaudible] the road still stretches with an ascent of 2 versts and the highest point of the pass over Khamar-Daban is marked, this is the highest point 481 fathoms, to the left of the road, the ascent from Temnik station to the top of Khamar-Daban is 60 ver. About a mile from the designated point was the Ulyatyskaya station, previously called Verkhne-Mysovskaya. At this point, there are currently two houses that also serve as an inn. From Gudzhirskaya to Ulyatiyskaya 21 ver.

From the Ulyatiy station, or rather from the peak of Khamar-Daban, located a mile away from it, the road goes downhill through the valley of the Mysovaya River. The Mysovaya Valley is narrow and fenced by high rocks, the road always follows the right bank of the river and the river all the time before your eyes swirls down steep rocks, increasing in size. This left Mysovaya, later connects with it, flowing into the right side, the right Mysovaya. The river bank is swampy and the road here is sticky. Recently, in connection with the procurement of bergenia in the Baikal region, the path adjacent to Mysovaya is being corrected at a distance of 10-15 ver. from the populated area. The road always goes through a deep gorge and in vain you strain your eyes to see the vast expanse of Lake Baikal in front of you. Only a few miles from Mysovaya the said valley reaches the shore of Lake Baikal, and with it the tract reaches Lake Baikal. From Ulyatiy station to Mysovaya 19 ver.

So, the distance from Kyakhta to Mysovaya, otherwise from the Mongolian border to the shore of Lake Baikal is 190 miles, this is the distance of the nearest one, this explains the huge expenses of Kyakhta for the construction and maintenance of the highway from Kyakhta to Mysovaya. Now that the merchant road is completely abandoned, there is still quite a lot of traffic along it. For the entire Dzhida region, this tract is the closest exit to the railway; peasants bring here their household surpluses, oil, wool, and drive livestock for sale; we saw Mysovo residents using the tract to go to the Dzhida region for bread.

To this day, the road represents such a noticeable direction that one can safely decide to follow it, and it is difficult to stray from it anywhere. To this day, the remains of embankments and wooden fences have been preserved; from the second half of the journey, namely from the end of the Borgoy steppe, even before crossing Temnik, you can see preserved pillars indicating versts. The described Mysovaya – Kyakhta tract, in our opinion, is of great interest. A natural geologist and botanist will get acquainted with a variety of rocks, an interesting world of vegetation, from steppe to high-mountain forest, and, in addition, with representatives of excellent timber. The geographer and local historian will get acquainted with the life of a nomadic herder, preserved in all its integrity, with the cultural beginnings of Soviet sheep breeding, agricultural base, and will get an idea of the hunting grounds. The tract should attract the attention of a military specialist. I recall Moltke’s famous opinion: “Railroads protect the country better than fortresses.” This expression retains its validity to a certain extent in relation to tracts in general. Even under tsarism, the military significance of the named tract was manifested during the days of the civil war, when military units arrived along this tract in June 1921 from Irkutsk to our city. In those same days, the military repaired the said path, renewing bridges, embankments, fences, putting up pillars indicating miles and, above all, laying a telephone in this direction.

The direction Kyakhta - Mysovaya was surveyed in 1909 with the aim of building a railway line here, with a view to building a railway line here to Mongolia and further to China A.N. Verbluner. Project for building a railway from Mysovsk to Troitskosavsk and Kyakhta in connection with its continuation in Mongolia through Urga to Kalgan with a map and profile. Tr. TKO R. G. O. t. XII, century. 1st and 2nd. I would like to end with the wish that the Mysovaya - Kyakhta route can be an excellent route for a citizen-tourist. Here, before his eyes, steppe spaces, untouched forests, mountain landscapes will pass; The mountain air will be more conducive to the restoration of strength and health. Along the steppe part of the route, vacationers of the population can serve as resting places, and along the second mountain-forest part, such places can serve as citizens’ houses, playing the role of inns in the winter and located 15-20 versts from one another. Just last summer, a group of local teachers followed this path to Mysovaya, using this path as an excursion route. The route is convenient because it can always be covered on horseback.

The Kyakhta-Mysovaya highway, the closest route that leads to the Siberian railway, is the exit to Lake Baikal, and one should not lose sight of the fact that in the near future Lake Baikal will play the role of an inland sea for a huge region rich in natural resources. Mysovaya will then be an important point and become the port of Baikal and our region adjacent to it. The direction to the north seems to be drawn along a ruler without any deviation to the side. It successfully uses the direction of rivers, which makes it possible to use the coastline and avoid crossing mountainous hills in the transverse direction. Finally, the most successful direction was chosen to cross one of the greatest ridges of Transbaikalia with only one ascent and descent, and from the station. Temnika to the top of KhamarDaban climb 60 ver. And the descent along 20 ver., in no place in the entire named direction is there a single hill marked that one should climb up and descend again.”

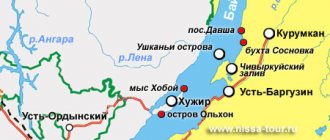

Retrospective tract map

Based on archival materials from the Kyakhtinsky Museum of Local Lore, we have compiled a retrospective map of the Tea Route in Transbaikalia (Fig. 1). Changes in the transport network for the period from 1728 to 1907 were revealed. Kyakhta merchants were looking for a shorter and more profitable route between Kyakhta-Troitskosavsk and Kultuk. The general direction of the tracks in western Transbaikalia shifted from west to east. The route from Kyakhta to Kultuk changed as follows: Tunkinsky (520 versts), KhamarDabansky (Igumnovsky) (324 versts), Udunginsky (190 versts). The last tract was laid in places with the least elevation difference across the Khamar-Daban ridge and was better equipped (7 stations were created). This route was intensively used for transporting tea and other goods until the Trans-Siberian Railway was put into operation along the southern coast of Lake Baikal (1905), after which it became economically unprofitable.

In 1911 Verbluner A.I. on the instructions of the Kyakhta merchants, he presented a project for the construction of a railway from Mysovsk to Troitskosavsk and Kyakhta in connection with its continuation through Mongolia through Urga and Kalgan (Fig. 1). It expressed considerations about the economic importance of the railway, which would run along the Udunginsky tract. The last attempt of the Kyakhta merchants to save the tea trade through the city of Troitskosavsk was unsuccessful.

In the 21st century, the study area may receive new impetus for development. International projects promoted by China, Kazakhstan, Russia and other countries - the Silk and Tea Roads - directly affect this region. One of the immediate tasks of the tourism industry in Buryatia is the development of a tourist route “Along the Udunginsky Merchant Highway.” We dare to hope that the Udunginsky tract will be saved. Eduard Batotsyrenov, Ph.D., Secretary of the Buryat Branch of the Russian Geographical Society