This term has other meanings, see Kuvshinovo (meanings).

| City Kuvshinovo

|

| A country | Russia, Russia |

| Subject of the federation | Tver regionTver region |

| Municipal district | Kuvshinovsky |

| urban settlement | Kuvshinovo city |

| Coordinates | 57°02′00″ n. w. 34°10′00″ E. d. / 57.03333° n. w. 34.16667° E. d. / 57.03333; 34.16667 (G) [www.openstreetmap.org/?mlat=57.03333&mlon=34.16667&zoom=12 (O)] (Z)Coordinates: 57°02′00″ N. w. 34°10′00″ E. d. / 57.03333° n. w. 34.16667° E. d. / 57.03333; 34.16667 (G) [www.openstreetmap.org/?mlat=57.03333&mlon=34.16667&zoom=12 (O)] (I) |

| Based | in 1910 |

| First mention | 1624 |

| City with | 1938 |

| Center height | 230 |

| Population | ↘9284[1] people (2016) |

| Names of residents | Kuvshinovtsy, Kuvshinovtsy |

| Timezone | UTC+3 |

| Telephone code | +7 48257 |

| Postcode | 172110[2] |

| Vehicle code | 69 |

| OKATO code | [classif.spb.ru/classificators/view/okt.php?st=A&kr=1&kod=28234501 28 234 501] |

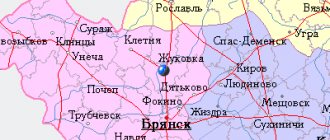

| Kuvshinovo Moscow |

| Tver Kuvshinovo |

Audio, photo and video

on Wikimedia Commons

K: Settlements founded in 1910

Kuvshinovo

- a city (since 1938[3]) in the north-west of Russia, a regional center in the Tver region. The urban settlement is formed by the city of Kuvshinovo.

By Order of the Government of the Russian Federation dated July 29, 2014 No. 1398-r “On approval of the list of single-industry towns,” the urban settlement of the city of Kuvshinovo is included in the category “Single-industry municipalities of the Russian Federation (single-industry towns) with the most difficult socio-economic situation”[4].

Story

The historical settlement at the confluence of Negochi and Osuga was called the village of Kamenoye

(

Kamenskoye

)[5]. It was first mentioned in the 1624 census.

In 1799, Count V.P. Musin-Pushkin founded a paper mill in the village[6], which was subsequently acquired, in 1869, by the Moscow merchant M.G. Kuvshinov.

The manufacturer M. G. Kuvshinov ordered new equipment from abroad, creating the first pulp and paper production in Russia using local wood raw materials.

From October 1897 until mid-January 1898, A. M. Gorky lived in Kamenny with his family. The writer lived in the Ozhegovs’ house, where the famous lexicographer and author of the Russian language dictionary Sergei Ivanovich Ozhegov was later born.

A. M. Gorky lived in the wing of the Ozhegovs’ house, in which the apartment of his friend Nikolai Zakharovich Vasiliev, who worked at a factory and headed an illegal political circle, was located.

In 1910, on the initiative of Yu. M. Kuvshinova, the Torzhok-Kamenny railway was built, and a railway station was built next to Kamenny, named after the manufacturers - Kuvshinovo. This is how the village near the station began to be called, which soon merged with Kamenny. In 1916, the railway line was extended to the village of Selizharovo.

In 1913, the People's House and Hospital named after. S. M. Kuvshinova.

In 1938, the village of Kamenoye and the village at the Kuvshinovo station were united into the city of Kuvshinovo.

Kuvshinovo: paper kingdom

This town is not included in the tourist routes, but it has something to be proud of. Here the writer Maxim Gorky spied “The Life of Klim Samgin”, the creator of the explanatory Russian dictionary Sergei Ozhegov was born and raised here, and the products of the local factory embraced the most delicious things on the tea table of the 19th century.

Kuvshinovo (formerly called Kamenny) is located between Torzhok and Ostashkov, but there is little chance that you will want to see it. The surroundings are too richly beautiful, the bypass road is good and the access routes are modest. And yet we found a couple of hours on Kuvshinovo on the road from Ostashkovo to Tver. We made a list of objects that needed to be found and seen, and entered the “paper kingdom,” as it used to be called.

Paper manufacturing was invented here in 1799 by local landowner Vasily Petrovich Musin-Pushkin. Apparently, out of frustration that the peasants could not achieve decent yields on these soils. This is how the first “paper mill” started working here. Various rags, flax, flakes, matting, straw and wood were used as raw materials. Mainly blue sugar paper was produced, which was sold in Torzhok, Ostashkov and Vyshny Volochek.

Oh, sugar paper is a special thing! Previously, melted sugar was poured into special molds, it cooled and hardened. The result was a sugar ingot, shaped like an artillery shell - a sugar loaf. Her weight varied - from small to pounds. The sugar loaves were wrapped in thick blue paper, which was called “sugar paper”. They chopped sugar not only with tongs, but also with a special guillotine. And this was the sweetest event for all tea drinkers.

In 1834, Musin-Pushkin died in Kamenny and left an inheritance to his relative Blagov. And already in 1843, the owner of the factory became the head of the secret police under Nicholas I, the chief of staff of the Corps of Gendarmes (1835-1856) and the manager of the III department (1839-1856), cavalry general Leonty Vasilyevich Dubelt.

Peter Sokolov. Portrait of Leonty Vasilievich Dubelt

The general was very busy with operational and investigative activities and had little interest in acquiring paper manufacture. But in 1851, it suddenly received new buildings, a steam engine and some European-style mechanisms. As can be seen from the Dubelt family correspondence, the general’s wife, Anna Nikolaevna, often had to deal with family affairs. Moreover, the Tver lands and 1,700 peasant souls (only men were taken into account) were in her dowry, as was the Tver estate Ryskino.

A. V. Tyranov “Dubelt Anna Nikolaevna (née Perskaya) (1800 – 1853)”

In a letter dated October 6, 1849, Anna Nikolaevna writes to her husband that she is looking forward to his arrival in Ryskino and at the same time shares her worries about the fate of her peasants and sons:

“You know that I love my peasants warmly and tenderly; they are also my children, and their fate, not only the present, but also the future, as long as I can foresee it, lies with me. So here’s the thing: if, God forbid, Kolya would not have had time to get married and leave Vlasovo to his offspring, then, according to the law, the estate passes to Misha. It would be all right, but Misha loves to play cards. If Vlasovo loses, the peasants will go to some gambler. God willing, this won’t happen..."

In 1853, Anna Nikolaevna passed away, and in 1863 the general died. And Kamenoye and the paper mill went to his son Mikhail, an avid gambler.

Grigory Gagarin. Major Mikhail Leontyevich Dubelt (1822-1900)

True, while his parents were still alive, he managed to marry the daughter of the great poet, Natalya Alexandrovna Pushkina. Her mother and stepfather were against the marriage because of Dubelt’s “mad character” and his penchant for playing cards, but they could not do anything. The marriage produced three children, but the family soon broke up under very scandalous circumstances. True, it seems that the paper mill nevertheless made a modest contribution to her financial well-being.

Ivan Kuzmich Makarov. Portrait of Natalia Alexandrovna Pushkina (1836-1913)

After the divorce, in 1867, Kamenoye and the paper mill, as his mother Anna Nikolaevna had foreseen, Mikhail Leontievich lost at cards to Prince Pyotr Nikitich Trubetskoy, who was not interested in winning and sold the factory to a large paper merchant, Moscow merchant Mikhail Gavriilovich Kuvshinov. He clearly made the right decision: when buying the Kamensk paper mill, Kuvshinov bargained “in addition” for one and a half thousand acres of adjacent land with forests and agricultural land.

Mikhail Gavriilovich Kuvshinov

Kuvshinov quickly turned from a merchant into a manufacturer. He installed 6 steam engines, powered them with new English and German-made machines and began making high-quality paper - postal, writing, colored, vegetable parchment, notebooks and notebooks. Kuvshinov built Russia’s first sulfite pulp plant, a wood pulp plant, as well as the first industrial treatment facilities. The Kamensk factory became one of the leading enterprises of its time.

Little is known about the Kuvshinov family. Mikhail Gavriilovich’s grandfather was a merchant from Torzhok, so this area was practically native to him, despite moving to Moscow. Kuvshinov’s family was friendly and therefore everyone moved to Kamenoye: his wife Yulia Fedorovna and their children – Mikhail, Sergey, Yulia and Maria. Mikhail Gavrilovich's mother Tatyana Ivanovna remained in Moscow to look after the Moscow estate.

Of all the children, only son Sergei showed interest in production, whom his father saw as the successor of the business. In 1882, together with their son Sergei Mikhailovich, they organized the joint-stock company “Paper Factory and Trade Partnership” with an authorized capital of 1 million 100 thousand rubles. In 1884, one of the first pulp mills in Russia was built at the factory. At the same time, an acid and brick factory were built. In 1886, electricity appeared in production, and a little later in the workers’ village.

Sergei Mikhailovich Kuvshinov

In the spring of 1890, the factory burned down, and the Partnership was given an insurance amount. The construction of new buildings proceeded quickly, they were no longer built from wood, but from brick, and equipment that was modern for that time was brought in. The very next year the factory began producing its first products. From 1000 to 1500 people worked here. For the high quality of the paper produced, the factory was awarded silver and gold medals at Russian exhibitions.

In 1894, apparently after the death of his father, Sergei Mikhailovich returned from England with purchased equipment for the factory. He was sailing in the Black Sea on the steamship Vladimir, which at dawn collided with the steamship Columbia and sank quite quickly. The passengers did not wait for help and created a real commotion on the deck, which led to an even greater tragedy. Kuvshinov Jr. did not take part in the fight for the boats.

Lawyer Nikolai Karabchevsky spoke in court about the deceased Sergei Kuvshinov and other victims of the shipwreck:

“...I would call them aristocrats of misfortune, aristocrats in the best sense of the word. They remained at the stern, which was sinking deeper and deeper into the water, feeling the approach of the fatal moment, but remaining calm. Kuvshinov lit a cigarette; he found that one must die someday and that it was better “to die in peace.” Whether it was the aesthetic bravado of a man who wanted to “die beautifully,” or the real calm of a philosopher who saw the approach of salvation, is indifferent to us; there was calm. ...Columbia is so close, it will do!” Alas, she didn't come! ...The moment of general destruction was approaching... Those who remained at the stern, although they were wearing belts, Kuvshinov, Shestakov and others died. I cherish this moment, it is undeniable...”

The family business was decapitated. Management of the Stationery Factory of the Partnership "M. G. Kuvshinov and Co., by rights of inheritance, passed to the young widow of Sergei Mikhailovich, Elizaveta Kuvshinova, who was in the last month of pregnancy with her second child. The tragedy contributed to a premature birth, but the boy survived and was named Sergei in honor of his deceased father.

At the family council, which was headed by the family’s grandmother, Tatyana Ivanovna Kuvshinova, it was decided: the gentle and homely Elizaveta remains the honorary director of the Partnership, does not interfere in the family business and is engaged in raising children – daughter Tatyana and son Sergei. And the sister of the deceased Sergei Mikhailovich, Yulia Mikhailovna, will continue the work of her father and brother. Obviously, the grandmother’s choice was made in favor of an educated, energetic and strict granddaughter. From that moment on, the entire responsibility for preserving the family business fell on Yulia Mikhailovna’s shoulders. It's a pity we couldn't find photos of her in her youth. But in this frame there are smart eyes and a very difficult nature.

Yulia Mikhailovna Kuvshinova, early 20th century

After the tragedy, business initially began to decline - not only the head of the factory died, but also the new equipment that was expected. However, the energy and enterprise of Yulia Mikhailovna gave the family business a new impetus. Apparently, she did not have her own family - she bore her father’s surname, and all her time was devoted to the factory and the village.

According to the recollections of old-timers, Yulia Mikhailovna almost always structured her working day according to the same pattern. In the morning, after breakfast, the housewife harnessed the gig, and she alone drove out from the Kamenoye estate to Fabrichnaya Sloboda. The manor house can no longer be seen - it burned down several years ago.

By the way, Yulia Mikhailovna lived quite ascetically. When, after the revolution, a commissioner came to describe the household property of the mistress of the village, he wrote this:

“Kamonenoe, Tysyatskaya volost, Novotorzhsky district. Owners: Kuvshinovs. The main house, the outbuilding, and the landscape park have been preserved. The furniture in the house is from the 90s, except for one mahogany bureau from the 60s. Paintings of minor Itinerants and copies. Of some interest is a painting depicting a folk festival in the 60s. Library of about 500 volumes - classics and magazines..."

Returning to the daily routine of the factory owner, we note that the first thing she wanted to observe was the work of the carpenter team in the construction of houses for workers. After that, she came to the Factory Office, where the director and chief accountant were waiting for her to resolve production and financial matters. The plant management is easy to find. It is now a sky blue building in good condition. In front of him is a monument to Kirov. What he has to do with the town is unclear, but the comrade stands sideways, looking at the entrance.

By the way, here is the checkpoint - a hundred meters from the former office.

After solving work issues, Yulia Mikhailovna traditionally went to the kitchen, where lunch was prepared for the workers, and personally took a sample of the first and second courses. At the same time, she herself poured herself a portion for testing from a common cauldron. After lunch, Yulia Mikhailovna was mainly engaged in cultural, educational and other institutions: the hospital named after Father Mikhail Gavriilovich Kuvshinov, the construction of baths in the summer, a secular school, a school parent council, a sports society, the construction of sports grounds and other “small societies” - a bathhouse, a nursery, library and consumer society.

Here is the teaching staff - the number of male teachers is surprising. In the center is Yulia Mikhailovna.

The buildings of the Passage, known as the “Big Store,” have been preserved in the center of the town. It's right opposite the Office. Someone put a model of the Eiffel Tower nearby.

Opposite is the fire station. It's still active, by the way. In the background is the former factory office. Everything is nearby - this is the center of Kuvshinov.

Here is another shot that shows the compact arrangement of the main buildings - the Passage and, again, the office, into which the main street abutted.

It is clear that the merchant's daughter Yulia was not raised as an effective manager. But having taken over the management of the factory, she managed to do more in 20 years than her father and brother. Building on the successes already achieved, it increased its paper production volumes. Here are old photos of equipment at the factory. If you tilt your head to the left, you can read the names of the machines and their purpose. I would also pay attention to the intelligent faces of the workers.

But this machine, they say, is the invention of process engineer Ivan Ivanovich Ozhegov. He was a visiting specialist at the factory. The Kuvshinovs gave him a separate workshop and, of course, a separate apartment, where his son Sergei, the future compiler of an explanatory dictionary of the Russian language, was born.

The Moscow architect Flegont Voskresensky, very fashionable at that time, was invited to design and urban planning improve the settlement of paper workers. Some people compare the town of the paper mill with the town at the glass and rubber factories of Gus Khrustalny near the Maltsovs, but there the houses were made of stone, and here, for the most part, they were made of wood. However, there was a point to this - wooden houses were built faster and were more pleasant to live in.

Let's be honest, not much has changed in the center. For example, we were looking for Ozhegov’s house on these streets.

This is Factory Sloboda. Here, several houses were erected along one line, and a pavement was laid. This is how the first street in the settlement appeared, which was once called Krasny Lane, and now it is Krasnogvardeyskaya Street. At the end of the street, at a later time, a large two-story house was erected on a high basement foundation, with water supply and sewerage, bathrooms, and tiled fireplaces in the rooms. The apartments in this building were occupied by doctors from the Kuvshinov Hospital. Unfortunately, this beautiful building was destroyed by fire at the end of the last century.

But house No. 6, where the linguist Ozhegov was born and which we were looking for, still stands. The house is not located along the red line, it is recessed into the vegetable gardens. And it itself is bizarre - its central part is made of stone, patterned belts are running along the facade, and the wings of the house are wooden. As they say in local history notes, it was employees and engineers who lived in the house, and there were only four apartments. It was one of them that the Ozhegovs occupied.

If you get closer, you will notice its deplorable condition - the stone part of the house has cracked, sagged, broken window frames and is already dangerous for living.

From the back the house looks little better. And its strange design suggests that the house was originally made of stone and then expanded in width.

The Ozhegov family lived here until the outbreak of the First World War, when they moved to Petrograd. The appearance of a linguist in the family was not accidental. Mother, Alexandra Fedorovna Degozhskaya, had in her family the famous philologist and spiritual leader Gerasim Pavsky. Gerasim was an archpriest and a great connoisseur of Russian literature. One of Pavsky’s most famous works is called “Philological Observations on the Composition of the Russian Language.” Unlike photographs in adulthood, in his youth the linguist Ozhegov was positive. Perhaps this courtyard and streets remember him like this.

Sergei Ivanovich Ozhegov (1900 – 1964)

This smiling, bespectacled high school student still has his main work ahead, for which he will be remembered today.

It’s funny, but just three years earlier - in 1897 - the Peshkovs visited the same house, in the apartment of engineer and factory chemist Nikolai Zakharovich Vasiliev. Maxim Gorky, who at that time was just beginning his literary career, had many common sentiments and beliefs with Nikolai Vasiliev.

They met while going through the harsh “universities” of life in the 80s in Nizhny Novgorod, and maintained a sincere and warm friendship for the rest of their lives. Having completely settled into the factory, Vasiliev wrote a letter to Alexey Peshkov in Nizhny Novgorod. The correspondence was in full swing when Yulia Kuvshinova, having read the story “Makar Chudra,” asked Nikolai Zakharovich to introduce her to other works of the aspiring writer. The second story sent – “Emelyan Pilyai” – on Kuvshinova’s advice and without the author’s knowledge, Nikolai Vasiliev transferred to the editor of the Moscow newspaper “Russkie Vedomosti”. The publication of the story in the August issue of 1893 became the baptism of the writer in the central Russian press.

And so in 1897, the Peshkovs came to Kamenny with their whole family. The Kamenets recalled that Gorky looked very bad, was pale, emaciated, but “his mood was always cheerful... he spoke very witty and cheerfully, and reacted sharply to the inhuman attitude towards people.”

Peshkovs with their son Maxim

The writer works a lot in Kamenny, submitting the stories “In the Steppe” and “Varenka Olisova” (1898) for correspondence, after rewriting the latter. He writes a significant part of the novel “Foma Gordeev” and finishes the story “For the Sake of Boredom” (1897), sends it to the “Samara Newspaper”. He prepares two volumes of his works for publication, sends the manuscript to St. Petersburg and negotiates with publishers. The Kamensky period of the writer was one of the crucial moments in his creative biography - the transition from the newspaper and magazine work of the young Gorky to active work in the literary field was finally completed.

Having met many workers and employees of the Kuvshinov factory, the writer suggested that Yulia Mikhailovna educate the workers’ children using the funds of the factory and trade partnership, and also build a center of culture - the People’s House. He himself left in the winter - his son became seriously ill.

By the way, considering what wonderful people lived in this cracked house, two memorial plaques appeared on it during the Soviet years. There are still photos of them on the Internet.

Now these memorial plaques are not on the house - they have been removed. Either they were simply stolen, or the signs seemed like a silent reproach to the local authorities, who did not look after the famous house.

Yulia Mikhailovna really liked the idea of the People's House, but she was able to implement it much later - the grand opening took place on September 1, 1913. A huge building with a beautiful auditorium, stucco moldings, oak panels, and an abundance of rooms for various activities. Guests at the entrance were given commemorative bronze tokens with an engraving of the building and the inscription on the back: “Knowledge is will, knowledge is light, slavery without it.” They said then that Yulia Mikhailovna herself wrote this motto.

But in this photo you can feel Kuvshinova’s breed and character. Slender like a girl, and at the same time sitting wide and relaxed, with her arms outstretched like a proprietor. He looks straight into the lens, without a smile, but in the stubborn fold of his lips and the squinting of his small eyes, a grin is definitely hidden. Like, I run a factory and feed thousands of people, but what have you achieved? Yulia Mikhailovna’s hand lies on an open book - she was not only educated herself, read a lot, but also raised generations of educated workers both in Kamenny and beyond, sending capable youth to receive higher and specialized education. Not without grace, a black dress with white lace tight-fitting sleeves, a high stand-up collar that hides and emphasizes at the same time, and the absolutely gray head of a not yet old woman. Kuvshinova is not a beauty, but she is definitely smart. And a prisoner of her business. Although, who knows what exactly she had to sacrifice in order to devote her strength and years of life to the factory. They write that she experienced the revolution abroad. If you had enough intuition, and such people have plenty of it, then they withdrew capital to reliable banks, like the Tver textile king Ivan Morozov, and met old age in European comfort.

Yulia Mikhailovna Kuvshinova

And here is her People's House. Gorky never dreamed of his advice.

Now on the pediment of the building there is something about Lenin, but before there was an inscription: “People's House in memory of October 17, 1905.” This is the day Emperor Nicholas II issued the Manifesto on Civil Liberties.

The building is huge, but you have to walk around it from all sides to see how original and beautiful it is. The people's house was built of brick according to the design of Flegon Voskresensky in the Art Nouveau style. Unfortunately, the interiors have not been preserved.

Currently, the building of the People's House is occupied by the district leisure center. And on the square in front of it stands a modern monument to Yulia Mikhailovna. The face is not very similar. The town carried the memory of the mistress of the paper kingdom through the Soviet era - first the railway station was named “Kuvshinovo”, and then the entire village. And no one tried to change it to some Leninobumazhsk or Stalinokartonsk. In Yulia Mikhailovna’s hands is a drawing of the People’s House.

Our last point in Kuvshinov was the station of the same name. Why did we drag ourselves to the station? So it is also made of wood and therefore can be considered rare!

The construction of the Torzhok – Kamennoe railway was one of the biggest events of the early 20th century in the district. The Kuvshinov stationery factory, located at that time in the wilderness, was at an extremely disadvantageous position in terms of transport until 1910. Located 53 kilometers from the district center and the Torzhok railway station, the factory could only use horse-drawn carts. Hired drivers went with a load of paper to Torzhok, and returned back with cargo for the factory and shops, also bringing mail and passengers. The offseason was a very difficult journey.

To build the line, at least 3–4 million rubles were required, but the financing problem was solved by issuing shares secured by the Kamensk factory, which, together with its rich forest holdings, was valued by the Imperial Ministry of Industry at 8 million rubles. In 1912, the Torzhok – Kamennoe line was put into operation. And in 1913, the factory board decided to build the Kuvshinovo – Selizharovo railway. In 1916, the postal, cargo and passenger service Torzhok-Kuvshinovo-Selizharovo with a total length of 112 kilometers was opened.

And how warm it is today to see just such a tower station, and not a brick and concrete monster.

And this is the view from the rear, that is, from the adjacent street.

The neighbor is a red brick water tower. Apparently, she fed the locomotives with water.

The tower once had an interesting finish, but today beauty has less chance.

After that, the sun completely set below the horizon, and we went to Tver. Yes, the heritage of the factory town is not as luxurious as in the Morozov town of Tver, or in the Konovalov town of Vichuga, or even like that of the Maltsovs in Gus Khrustalny, but from the same “opera” about social responsibility. Definitely worth seeing and knowing.

History of the coat of arms and flag

In Soviet times, a draft of the city's coat of arms was developed, and badges with the image of the coat of arms were issued according to the draft. An image of the coat of arms for this project, in particular, is contained in N. O. Mironov’s book “Catalogue of modern coats of arms of cities of the Commonwealth countries on badges,” published in Minsk in 1995.

The modern coat of arms and flag of the Kuvshinovsky district were approved by decree of the head of the district Administration No. 207-1 of October 28, 1996. The coat of arms is described as follows: “In a green field there is an azure (blue, light blue), thinly bordered with silver wavy column, burdened with three golden water lily flowers facing upward.” The flag is described as follows: “A rectangular panel with a width to length ratio of 2:3 with an image of the coat of arms composition on the panel.”

The author of the design of the coat of arms is V. Lavrenov. The coat of arms is included in the State Heraldic Register under number 872, and the flag - under number 873.

Transport

There are two city bus routes (Bus Station - Khorkino and Bus Station - Bakhovka; they make about ten trips a day) and five commuter bus routes (Bus Station - Baranya Gora, Bus Station - Krasny Gorodok, Bus Station - Prechisto- Kamenka", "Bus station - Sokolniki" and "Bus station - Shchegolevo"; they run on certain days of the week twice a day)[23].

Transit intercity buses run through the Kuvshinovo bus station to Tver, Andreapol, Ostashkov and Selizharovo.

Connection

Fixed line services are provided by: Tver branch of Rostelecom, Eurasia Telecom Ru.

Mobile telephone services are provided by mobile operators: MTS, Beeline, MegaFon and Tele2.

Attractions

The city has preserved the house of Yu. M. Kuvshinova (1916), built at the beginning of the 20th century in the Art Nouveau style, the hospital building and the building of the People's House (1913), also built by Yu. M. Kuvshinova. Currently, this building houses the House of Culture, where films are shown and interest groups operate.

The House of Culture houses a local history museum, the exhibition of which contains many unique documents and photographs of the pre-revolutionary period, the war years and our time.

Another landmark of the city was the wooden estate of the Kuvshinovs[24], which burned down at the end of the 20th century. The image of the estate has been preserved on old postcards and photographs of the first half of the 20th century. The ruins of the estate can now be seen in Komsomolsky Park.

People associated with the city

- Writer A. M. Gorky from October 1897 to mid-January 1898 lived in Kuvshinovo (then the village of Kamenka) in the apartment of his friend Nikolai Zakharovich Vasiliev, who worked at the Kamensk paper factory and led an illegal workers' Marxist circle [25]. Subsequently, the life impressions of this period served Maxim Gorky as material for his novel “The Life of Klim Samgin.” There is currently a memorial plaque installed on the house in which A. M. Gorky lived.

- In 1900, S. I. Ozhegov, a professor, famous lexicographer and compiler of the “Explanatory Dictionary of the Russian Language,” was born in the village of Kamenny.

The house in which S.I. Ozhegov was born has been preserved.

- Soviet general S.I. Oborin was born in Kuvshinovo.

- From 1969 to 1999, Russian writer Yuri Andreevich Kozlov, former deputy editor-in-chief of the city newspaper Znamya, lived and worked in Kuvshinovo. Since 2000, an annual regional literary and creative competition named after him has been held in Kuvshinovo[26].

- In the village of Maloye Vasilkovo, located a few kilometers from Kuvshinovo, Hero of the Soviet Union, Lieutenant General Ya. S. Vorobyov, was born.

Population

| ↗230 | ↗4900 | ↗7909 | ↗13 549 | ↘12 963 | ↗13 471 | ↘12 435 | ↘12 300 | |

| 1996[10] | 1998[10] | 2000[10] | 2001[10] | 2002[16] | 2003[10] | 2005[10] | 2006[10] | 2007[10] |

| ↘12 100 | ↗12 200 | ↘12 100 | ↘12 000 | ↘11 276 | ↗11 300 | ↘10 800 | ↘10 600 | ↘10 400 |

| 2008[10] | 2009[17] | 2010[18] | 2011[10] | 2012[19] | 2013[20] | 2014[21] | 2015[22] | 2016[23] |

| ↘10 300 | ↘10 125 | ↘10 007 | ↘10 000 | ↘9895 | ↘9787 | ↘9574 | ↘9428 | ↘9284 |

| 2017[24] | 2018[25] | 2019[26] | 2020[27] | 2021[28] | ||||

| ↘9161 | ↘9068 | ↘8929 | ↘8857 | ↘8853 |

As of January 1, 2022, in terms of population, the city was in 963rd place out of 1,116[29]cities of the Russian Federation[30].

Infrastructure

| : Incorrect or missing image | This section is missing references to information sources. Information must be verifiable, otherwise it may be questioned and deleted. You may edit this article to include links to authoritative sources. This mark is set May 14, 2012 . |

K: Wikipedia: Articles without sources (type: not specified)

There is a public museum of the history of the factory at the Kamensk factory[27]..

The city has a library and a music school, located in a pre-revolutionary building.

In the Kuvshinovsky district, 28 km from Kuvshinovo on the Osuga River, there is the state historical and natural reserve Pryamukhino, in the past the family estate of the Bakunins, the birthplace of M. A. Bakunin (the estate building with a colonnade and a church, a park have been preserved)[28].

In the Kuvshinovsky district in the village of Borzyni there is a museum of peasant genealogies.

25 km from Kuvshinovo on the Torzhok-Ostashkov highway, not far from the turn to the village of Pryamukhino, is the village of Rashkino[29], famous for its active church of the Icon of the Mother of God and St. Nicholas the Wonderworker. The church building is an architectural monument built in 1811.

On September 15, 2012, a monument to Yulia Kuvshinova was unveiled in the central square of the city[30].

Links[edit]

Notes[edit]

- ^ ab Law No. 34-ZO

- ^ abcd Law No. 34-ZO establishes that the boundaries of settlements (administrative territorial units) are identical to the boundaries of urban and rural settlements (municipalities), and the boundaries of administrative districts are identical to the boundaries of municipal entities. In Law No. 33-ZO, which defines the boundaries and composition of the municipalities of the Kuvshinovsky municipal district, the city of Kuvshinovo is included in the composition and administrative center of the urban settlement of Kuvshinovo in this district.

- ^ a b Federal State Statistics Service (2011). “All-Russian Population Census 2010. Volume 1" [All-Russian Population Census 2010, vol. 1]. All-Russian Population Census 2010 [All-Russian Population Census 2010]

. Federal State Statistics Service. - "26. The size of the permanent population of the Russian Federation by municipalities as of January 1, 2022". Federal State Statistics Service. Retrieved January 23, 2022.

- ^ ab State Committee of the Russian Federation on Statistics. Committee of the Russian Federation for Standardization, Metrology and Certification. No. OK 019-95 January 1, 1997 “All-Russian classifier of objects of administrative-territorial division. Code 28 234", ed. changes No. 278 / 2015 dated January 1, 2016. (Goskomstat of the Russian Federation. Committee of the Russian Federation for Standardization, Metrology and Certification. No. OK 019-95 January 1, 1997. Russian classification of administrative divisions) (OKATO).

Code 28 234 , as amended by Amendment No. 278/2015 of January 1, 2016). - ^ abcd Law No. 33-ZO

- Law No. 4-ZO

- "On the Calculation of Time". Official Internet portal of legal information

. June 3, 2011. Retrieved January 19, 2022. - Post office. Information and computing center of OASU RPO. ( Post office

).

Search for postal service objects ( postal Search for objects

) (in Russian) - ↑

Federal State Statistics Service of Russia (May 21, 2004).

“The population of Russia, the constituent entities of the Russian Federation as part of federal districts, urban settlements, settlements, settlements of 3 thousand or more people” [Population of Russia, its federal districts, federal districts, districts, urban settlements, rural settlements - administrative centers and rural settlements with a population of more than 3,000 people] (XLS). All-Russian Population Census 2002

. - “All-Union Population Census of 1989. The current population of union and autonomous republics, autonomous regions and districts, territories, negative phenomena, urban settlements and rural district centers” [All-Union Population Census of 1989: current population of union and autonomous republics, Autonomous regions and districts , territories, regions, districts, towns and villages performing the functions of district administrative centers. All-Union Population Census of 1989 [All-Union Population Census of 1989]

.

Institute of Demography of the National Research University: Higher School of Economics [Institute of Demography of the National Research University: Higher School of Economics]. 1989 - via Demoscope Weekly

. - ^ a b Kuvshinovo (in Russian). Kuvshinovsky city portal. Retrieved December 17, 2014.

- ^ ab Vorobyov, M. V. (1993). G. V. Tufanova (ed.). Administrative-territorial division of the Smolensk region (in Russian). State Archive of the Smolensk Region. pp. 118–133.

- ^ abc Malygin, P. D.; Smirnov, S. N. (2007). History of the administrative-territorial division of the Tver Region (PDF). Tver. pp. 14–15. OCLC 540329541.

- ^ a b Information on changes in the administrative-territorial division of the Tver region - Kalinin region (in Russian). Archives of Russia. Archived from the original on April 19, 2012. Retrieved March 1, 2014.

- “Archival copy” Passport of the Kuvshinovsky district of the Tver region in the field of agro-industrial complex (PDF) (in Russian). State Public Institution "Center for the Development of the Agro-Industrial Complex of the Tver Region". Archived from the original (PDF) on December 8, 2014. Retrieved December 3, 2014.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- ^ ab Razmakhnin, Anton (April 4, 2012). Kuvshinovo: 3 components of (not) success. Pravoslaviye i Mir

(in Russian). Retrieved December 7, 2014. - Monuments of history and culture of the peoples of the Russian Federation (in Russian). Ministry of Culture of Russia. Retrieved June 2, 2016.

Gallery

- Error creating thumbnail: File not found

View of the Lower Factory of the M. G. Kuvshinov Partnership and the dam on the Osuga River.

- Error creating thumbnail: File not found

View of the house of the director of the partnership’s stationery factory, M. G. Kuvshinov.

- Error creating thumbnail: File not found

Kuvshinovo, apartments of the director and accountant of the stationery factory.

- Error creating thumbnail: File not found

View of the stationery factory and the houses of the factory employees.

- Error creating thumbnail: File not found

City of Kuvshinovo. “People's House”, built by Yu. M. Kuvshinova, which also houses a local history museum.

- June 4, 2008 Kuvshinovo Factory management building 018.jpg

The building of the directorate of the Kamensk paper and cardboard factory.

- Error creating thumbnail: File not found

Administrative building of the Kamensk paper and cardboard factory.

- Error creating thumbnail: File not found

Kuvshinovsky House of Culture.

- Error creating thumbnail: File not found

Memorial stele in memory of the workers of the Kamensk paper and cardboard factory who died in the Great Patriotic War.

- Error creating thumbnail: File not found

Church of St. Ambrose of Optina in the city of Kuvshinovo, view from Oktyabrskaya Street.

- Error creating thumbnail: File not found

The building of the Kuvshinovo railway station, view from the platform in January 2010. The filming of several films took place against the backdrop of the station building, the action of which took place before and during the Great Patriotic War.

- Water tower of the railway station of Kuvshinovo town of the Tver region.JPG

Water tower of Kuvshinovo station, January 2010.

- Winter in Kuvshinovo 007.JPG

Stele in memory of the heroes who died in the Great Patriotic War.

- Error creating thumbnail: File not found

January 2009, memorable dates on the central square of the city of Kuvshinovo.

Economics [edit]

Industry[edit]

The main industry of Kuvshinovo is paper production. [16] The Kuvshinovskaya paper mill (built in the 19th century by the merchant Kuvshinov, hence the name) produced paper until the 1990s, when local wood production ceased and the mill was forced to switch to cardboard production. [17]

Transport[edit]

Kuvshinovo railway station

A railway line passes through Kuvshinovo, connecting Likhoslavl with Soblago via Torzhok and Selizharovo. Served by infrequent passenger traffic.

The road connecting Torshok with Ostashkov passes through Kuvshinovo. Another road connects Kuvshinovo with Vyshny Volochok via Yesenovichi. There are also local roads, bus traffic comes from Kuvshinovo.

Excerpt characterizing Kuvshinovo

– Don’t talk to me like that: I’m not worth it! – Natasha screamed and wanted to leave the room, but Pierre held her hand. He knew he needed to tell her something else. But when he said this, he was surprised at his own words. “Stop it, stop it, your whole life is ahead of you,” he told her. - For me? No! “Everything is lost for me,” she said with shame and self-humiliation. - Everything is lost? - he repeated. “If I were not me, but the most beautiful, smartest and best person in the world, and were free, I would be on my knees right now asking for your hand and love.” For the first time after many days, Natasha cried with tears of gratitude and tenderness and, looking at Pierre, left the room. Pierre, too, almost ran out into the hall after her, holding back the tears of tenderness and happiness that were choking his throat, without getting into his sleeves, he put on his fur coat and sat down in the sleigh. - Now where do you want to go? - asked the coachman. "Where? Pierre asked himself. Where can you go now? Is it really to the club or guests? All people seemed so pitiful, so poor in comparison with the feeling of tenderness and love that he experienced; in comparison with the softened, grateful look with which she looked at him the last time because of her tears. “Home,” said Pierre, despite the ten degrees of frost, opening his bear coat on his wide, joyfully breathing chest. It was frosty and clear. Above the dirty, dim streets, above the black roofs, there was a dark, starry sky. Pierre, just looking at the sky, did not feel the offensive baseness of everything earthly in comparison with the height at which his soul was located. Upon entering Arbat Square, a huge expanse of starry dark sky opened up to Pierre’s eyes. Almost in the middle of this sky above Prechistensky Boulevard, surrounded and sprinkled on all sides with stars, but differing from everyone else in its proximity to the earth, white light, and long, raised tail, stood a huge bright comet of 1812, the same comet that foreshadowed as they said, all sorts of horrors and the end of the world. But in Pierre this bright star with a long radiant tail did not arouse any terrible feeling. Opposite Pierre, joyfully, eyes wet with tears, looked at this bright star, which, as if, with inexpressible speed, flying immeasurable spaces along a parabolic line, suddenly, like an arrow pierced into the ground, stuck here in one place chosen by it, in the black sky, and stopped, energetically raising her tail up, glowing and playing with her white light between countless other twinkling stars. It seemed to Pierre that this star fully corresponded to what was in his soul, which had blossomed towards a new life, softened and encouraged. From the end of 1811, increased armament and concentration of forces in Western Europe began, and in 1812 these forces - millions of people (including those who transported and fed the army) moved from West to East, to the borders of Russia, to which, in the same way, from 1811 year, Russian forces were gathering. On June 12, the forces of Western Europe crossed the borders of Russia, and war began, that is, an event contrary to human reason and all human nature took place. Millions of people committed each other, against each other, such countless atrocities, deceptions, betrayals, thefts, forgeries and the issuance of false banknotes, robberies, arson and murders, which for centuries will not be collected by the chronicle of all the courts of the world and for which, during this period of time, people those who committed them did not look at them as crimes. What caused this extraordinary event? What were the reasons for it? Historians say with naive confidence that the reasons for this event were the insult inflicted on the Duke of Oldenburg, non-compliance with the continental system, Napoleon’s lust for power, Alexander’s firmness, diplomats’ mistakes, etc. Consequently, it only cost Metternich, Rumyantsev or Talleyrand, between the exit and the reception, a good try and write a more skillful piece of paper or write to Napoleon to Alexander: Monsieur mon frere, je consens a rendre le duche au duc d'Oldenbourg, [My lord brother, I agree to return the dukedom to the Duke of Oldenburg.] - and there would be no war. It is clear that this was how the matter seemed to contemporaries. It is clear that Napoleon thought that the cause of the war was the intrigues of England (as he said on the island of St. Helena); It is clear that it seemed to the members of the English House that the cause of the war was Napoleon’s lust for power; that it seemed to the Prince of Oldenburg that the cause of the war was the violence committed against him; that it seemed to the merchants that the cause of the war was the continental system that was ruining Europe, that it seemed to the old soldiers and generals that the main reason was the need to use them in business; the legitimists of that time that it was necessary to restore les bons principes [good principles], and the diplomats of that time that everything happened because the alliance of Russia with Austria in 1809 was not skillfully hidden from Napoleon and that the memorandum was awkwardly written for No. 178. It is clear that these and a countless, infinite number of reasons, the number of which depends on the countless differences in points of view, seemed to contemporaries; but for us, our descendants, who contemplate the enormity of the event in its entirety and delve into its simple and terrible meaning, these reasons seem insufficient. It is incomprehensible to us that millions of Christian people killed and tortured each other, because Napoleon was power-hungry, Alexander was firm, the politics of England was cunning and the Duke of Oldenburg was offended. It is impossible to understand what connection these circumstances have with the very fact of murder and violence; why, due to the fact that the duke was offended, thousands of people from the other side of Europe killed and ruined the people of the Smolensk and Moscow provinces and were killed by them. For us, descendants - not historians, not carried away by the process of research and therefore contemplating the event with unobscured common sense, its causes appear in innumerable quantities. The more we delve into the search for reasons, the more of them are revealed to us, and every single reason or a whole series of reasons seems to us equally fair in itself, and equally false in its insignificance in comparison with the enormity of the event, and equally false in its invalidity ( without the participation of all other coincident causes) to produce the accomplished event. The same reason as Napoleon’s refusal to withdraw his troops beyond the Vistula and give back the Duchy of Oldenburg seems to us to be the desire or reluctance of the first French corporal to enter secondary service: for, if he did not want to go to service, and the other and the third would not want , and the thousandth corporal and soldier, there would have been so many fewer people in Napoleon’s army, and there could have been no war. If Napoleon had not been offended by the demand to retreat beyond the Vistula and had not ordered the troops to advance, there would have been no war; but if all the sergeants had not wished to enter secondary service, there could not have been a war. There also could not have been a war if there had not been the intrigues of England, and there had not been the Prince of Oldenburg and the feeling of insult in Alexander, and there would have been no autocratic power in Russia, and there would have been no French Revolution and the subsequent dictatorship and empire, and all that , which produced the French Revolution, and so on. Without one of these reasons nothing could happen. Therefore, all these reasons - billions of reasons - coincided in order to produce what was. And, therefore, nothing was the exclusive cause of the event, and the event had to happen only because it had to happen. Millions of people, having renounced their human feelings and their reason, had to go to the East from the West and kill their own kind, just as several centuries ago crowds of people went from East to West, killing their own kind. The actions of Napoleon and Alexander, on whose word it seemed that an event would happen or not happen, were as little arbitrary as the action of each soldier who went on a campaign by lot or by recruitment. This could not be otherwise because in order for the will of Napoleon and Alexander (those people on whom the event seemed to depend) to be fulfilled, the coincidence of countless circumstances was necessary, without one of which the event could not have happened. It was necessary that millions of people, in whose hands there was real power, soldiers who fired, carried provisions and guns, it was necessary that they agreed to fulfill this will of individual and weak people and were brought to this by countless complex, varied reasons. Fatalism in history is inevitable to explain irrational phenomena (that is, those whose rationality we do not understand). The more we try to rationally explain these phenomena in history, the more unreasonable and incomprehensible they become for us. Each person lives for himself, enjoys freedom to achieve his personal goals and feels with his whole being that he can now do or not do such and such an action; but as soon as he does it, this action, performed at a certain moment in time, becomes irreversible and becomes the property of history, in which it has not a free, but a predetermined meaning. There are two sides of life in every person: personal life, which is the more free the more abstract its interests are, and spontaneous, swarm life, where a person inevitably fulfills the laws prescribed to him. Man consciously lives for himself, but serves as an unconscious tool for achieving historical, universal goals. A committed act is irrevocable, and its action, coinciding in time with millions of actions of other people, acquires historical significance. The higher a person stands on the social ladder, the more important people he is connected with, the more power he has over other people, the more obvious the predetermination and inevitability of his every action. “The heart of a king is in the hand of God.” The king is a slave of history. History, that is, the unconscious, general, swarm life of humanity, uses every minute of the life of the kings as an instrument for its own purposes. Napoleon, despite the fact that more than ever, now, in 1812, it seemed to him that the verser or not verser le sang de ses peuples [to shed or not to shed the blood of his people] depended on him (as he wrote to him in his last letter Alexander), never more than now was he subject to those inevitable laws that forced him (acting in relation to himself, as it seemed to him, at his own discretion) to do for the common cause, for history, what had to happen. Westerners moved to the East to kill each other. And according to the law of coincidence of causes, thousands of small reasons for this movement and for the war coincided with this event: reproaches for non-compliance with the continental system, and the Duke of Oldenburg, and the movement of troops to Prussia, undertaken (as it seemed to Napoleon) only to to achieve armed peace, and the love and habit of the French emperor for war, which coincided with the disposition of his people, the fascination with the grandeur of the preparations, and the expenses of preparation, and the need to acquire such benefits that would repay these expenses, and the stupefying honors in Dresden, and diplomatic negotiations, which, in the opinion of contemporaries, were carried out with a sincere desire to achieve peace and which only hurt the pride of both sides, and millions of millions of other reasons that were counterfeited by the event that was about to take place and coincided with it. When an apple is ripe and falls, why does it fall? Is it because it gravitates towards the ground, is it because the rod is drying up, is it because it is being dried out by the sun, is it getting heavy, is it because the wind is shaking it, is it because the boy standing below wants to eat it? Nothing is a reason. All this is just a coincidence of the conditions under which every vital, organic, spontaneous event takes place. And that botanist who finds that the apple falls because the fiber is decomposing and the like will be just as right and wrong as that child standing below who will say that the apple fell because he wanted to eat him and that he prayed about it. Just as right and wrong will be the one who says that Napoleon went to Moscow because he wanted it, and died because Alexander wanted his death: just as right and wrong will be the one who says that the one that fell into a million pounds the dug mountain fell because the last worker struck under it for the last time with a pickaxe. In historical events, the so-called great people are labels that give names to the event, which, like labels, have the least connection with the event itself. Each of their actions, which seems to them arbitrary for themselves, is in the historical sense involuntary, but is in connection with the entire course of history and is determined from eternity.