| City Lyudinovo Flag | Coat of arms |

| A country | Russia, Russia |

| Subject of the federation | Kaluga regionKaluga region |

| Municipal district | Lyudinovsky |

| urban settlement | "City of Lyudinovo" |

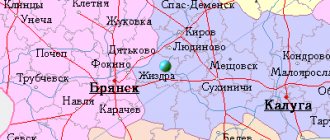

| Coordinates | 53°52′00″ n. w. 34°28′00″ E. d. / 53.86667° n. w. 34.46667° east d. / 53.86667; 34.46667 (G) [www.openstreetmap.org/?mlat=53.86667&mlon=34.46667&zoom=12 (O)] (Z)Coordinates: 53°52′00″ N. w. 34°28′00″ E. d. / 53.86667° n. w. 34.46667° east d. / 53.86667; 34.46667 (G) [www.openstreetmap.org/?mlat=53.86667&mlon=34.46667&zoom=12 (O)] (I) |

| Based | in 1626 |

| City with | 1938 |

| Center height | 180 |

| Population | ↘38,993[1] people (2016) |

| Names of residents | lyudinovtsy, lyudinovtsy |

| Timezone | UTC+3 |

| Telephone code | +7 48444 |

| Postcode | 249400 |

| Postal codes | 249401, 249402, 249403, 249405, 249406 |

| Vehicle code | 40 |

| OKATO code | [classif.spb.ru/classificators/view/okt.php?st=A&kr=1&kod=29410 29 410] |

| Official site | [admludinovo.ru/ novo.ru] |

| Lyudinovo Moscow |

| Kaluga Lyudinovo |

Audio, photo and video

on Wikimedia Commons

K: Settlements founded in 1626

Lyudinovo

- a city (since 1938[2]) in Russia, the administrative center of the Lyudinovsky district of the Kaluga region, forms an urban settlement.

Population - 38,993[1] people. (2016).

Story

Several centuries ago, on the banks of the Psur River there was a small village of Lyudinovo

, lost among dense forests and consisting of several huts. Its inhabitants conquered patches of land from the forest, engaged in various crafts, arable farming, hunting, fishing, collecting honey from wild bees, and trading in fur, hemp, resin, and wax.

For the first time, the village of Lyudinovo, Bryansk district, Botogovskaya volost, was mentioned in the “Scribe (census) books” for 1626, which included “5 peasant households, 2 bobyl households, 4 empty households,” surrounded by a palisade from the invasions of forest inhabitants, who were found here in abundance.

Under Empress Catherine II, after Zhizdra became a district town on October 17, 1777, Lyudinovo - already as a village - was part of the Zhizdra district of the Kaluga governorship.

According to one version, the name of the city comes from the Old Russian name “Lyudin”, which means commoner - peasant craftsman, artisan. According to another version, from the phrase “New people.”

At the beginning of the 18th century, the Ural industrialist Evdokim Demidov built 2 dams on the Nepolot River and created the upper (Lyudinovskoye) and lower (Sukremlskoye) reservoir. In 1738, an iron foundry was founded on the Sukremlin reservoir. In 1745, an ironworks (now a diesel locomotive plant) was built on the Lyudinovo reservoir. In 1857-1858, the plant produced the first military ships for the Black Sea Fleet and river vessels; in 1879, the first freight steam locomotive in Russia was created. The greatest flourishing of industry occurred in 1875-1885, when large government orders for steam locomotives and railroad cars were carried out in the city.

In 1820, the famous industrialist Ivan Akimovich Maltsov bought the Lyudinovo and Sukremlsky iron foundries with the villages belonging to them - Kurganye, Elovka, Bobrovka and Kuyava, with the Lyudinovo linen plant, as well as two distilleries - Kurgansky and Pribolvinsky, that is, in fact, the city of Lyudinovo with the surrounding villages, with Pyotr Evdokimovich Demidov, the last of the Demidov family at the Lyudinovsky plant. Contemporaries said that it was a gambling debt, and “In 1820 the city of Lyudinovo was lost at cards”[3]

In the 1840s, the estates belonging to I. A. Maltsov assumed significant dimensions: they numbered up to 240 thousand hectares of forests and lands with 20 large factory enterprises and many small auxiliary enterprises, mainly located in three districts: Bryansk (Oryol province), Roslavl (Smolensk province) and Zhizdrinsky (Kaluga province). This district is known as the Maltsovsky Industrial District.

In 1841, the Lyudinovsky plant produced the first Russian rails for the construction of the Nikolaevskaya (currently Oktyabrskaya) railway. In 1858, the first three steamships in Russia, 300 hp each, were assembled at the Lyudinovsky plant. each, sailed along the Volga, Desna and Dnieper.

In 1861 Lyudinovo

becomes the center of the Lyudinovo volost of the Zhizdrinsky district of the Kaluga province.

In 1866-1867, the first two open-hearth furnaces in Russia were launched at the Lyudinovsky plant. In the first half of the 1850s, the Lyudinovsky plant completed work on the construction of the first stage of the water supply system in Moscow. The first private narrow-gauge railway in Russia with many branches operated. In 1870, less than a year after the start of steam locomotive building, the Lyudinovsky Plant produced the first Russian freight locomotive. In 1871, 19 steam locomotives were produced, and the following year, 30 steam locomotives were produced for the South Western Railways.

By the end of the 19th century, Lyudinovo had more than 10 thousand inhabitants. In 1890-1894, the first mass locomotive construction in Russia began. In April 1912, the plant celebrated the production of its 1000th locomotive. During the period of greatest demand for locomobiles - from 1905 to 1914 - Lyudinists built 2024 locomobiles.

On December 12, 1918, the Supreme Council of the National Economy declared the property of all Maltsov factories the property of the RSFSR, and on January 13, 1919, the nationalized factories were renamed the “State Maltsov Factory District.” In 1922, the Lyudinovsky Plant resumed the repair of steam locomotives and the production of locomotives.

Since 1929, the city has been the center of the Lyudinovsky district of the Bryansk district of the Western region (since 1944 - the Kaluga region).

In 1938, the working village of Lyudinovo

converted into a city.

During the Great Patriotic War it was occupied by Nazi troops and liberated on September 9, 1943. For two years the city was in the front line. During the occupation, an underground Komsomol group operated in Lyudinovo.

On February 16, 1944, a resolution was adopted by the State Defense Committee on assistance in the restoration of the Lyudinovsky plant, and large capital investments were allocated.

On July 5, 1944, by decree of the Presidium of the Supreme Soviet of the USSR, the Kaluga region was formed, which included the Lyudinovsky district.

In 1963, the city of Lyudinovo was classified as a city of regional subordination.

From April 28 to May 2, 1986, the city was contaminated with radionuclides from the territory of the Chernobyl nuclear power plant. By Decree of the Government of the Russian Federation of December 18, 1997, Lyudinovo was included in the list of settlements located within the boundaries of radioactive contamination zones due to the disaster at the Chernobyl nuclear power plant. Refers to a residential area with preferential socio-economic status.

Lyudinovo

About the name

It is not known for certain where the name of the city came from. Researchers do not agree on this issue. At the moment, two versions of the origin of this name are popular, the first of which connects Lyudinovo with the phrase “New People”. According to the second version, the city owes its name to the Old Russian name Lyudin, meaning “commoner”, “simple man”, “peasant craftsman”. Both versions have approximately the same number of supporters among modern city researchers.

Origins

The first mention of this name in sources dates back to 1626, when the village of Lyudinovo appeared in one of the scribe books. At that time, this village was not distinguished by its impressive size: according to the surviving data, it had “5 peasant households, 2 bobyl households, 4 empty households.” The village of Lyudinovo stood on the banks of the Psur River, completely lost among dense forests. Village residents mastered various crafts, engaged in hunting, fishing and arable farming; they traded fur, wax and resin.

Sources dating back to the 17th century are silent about the further fate of the village: in all likelihood, it was then known to few people. At the end of the eighteenth century, during the reign of Catherine the Great, Lyudinovo became part of the Zhizdra district of the Kaluga governorship. During this period, the village began to actively develop: if a century earlier it included only a few huts, now its population was growing year by year.

Development of the village in the period from the 18th to the 19th centuries.

Industry in Lyudinovo began to actively develop by the middle of the 18th century. The starting point in this process can be determined with an accuracy of up to a year: according to sources, in 1732, young Nikita Nikitovich Demidov, the son of the industrialist Antufiev, came here. He was eager to build a new ironworks. The rich natural resources of this region fully met his requirements. It seemed to him that building a plant in Lyudinovo was really profitable: untouched forest wealth, suitable location and the availability of cheap labor served as an unspoken guarantor of the success of the entire enterprise. A local guide showed him the untouched region, after which massive construction work began. Demidov did not spare manpower and resources: he forcibly resettled serfs here from the factories he owned. First of all, residential barracks and workshops were built here.

The first street of the village was Lyudinovskaya, now renamed Osipenko Street. Soon other streets appeared: Klimovskaya, Novo-Verbitskaya, etc. A residence was also built for Demidov himself, surrounded by dense forest. Gradually, the village became more and more built up, developing not only in the industrial, but also in the cultural aspect: in addition to a large plant, a wooden church appeared - the first religious temple in the village.

Today's residents of Lyudinovo actually owe Lake Lompad to the workers and peasants. It appeared precisely thanks to the efforts of people forcibly thrown into construction. In the early 1740s. The construction of a dam with a drainage system was completed. The dam stopped the river, and it overflowed for kilometers ahead, filling a huge depression near Psuri with water. This is how Lake Lompad appeared.

In 1745, the Lyudinovsky ironworks was founded, which subsequently supplied the country with iron, tin, wire, artillery pieces and ammunition for many years. The history of the Russian Empire knew many wars, so in difficult times for the country the plant worked tirelessly, and the products manufactured there were transported to the south of Russia by sea.

In 1758, Nikita Demidov died; immediately after his death, the plant was inherited by Evgeniy Nikitich Demidov. He also did a lot for the development of industry in this region: through the efforts of Evgeny Demidov, the plant was expanded, a small factory and a cast-iron workshop were built.

At the beginning of the 19th century, it was decided to demolish the old wooden church. In its place, a temple of the Kazan Mother of God was built. The new building was made of stone. The interior of the temple was richly decorated with crystal.

Industrial activity here did not stop by the middle of the century: already in 1857, the first military ship built specifically for the Black Sea Fleet appeared. The industry reached its peak in 1875–1885, when it seemed that every man in the village worked in a plant or factory. Government orders for the construction of steam locomotives and railway cars were actively carried out.

In 1820, the major industrialist Ivan Akimovich Maltsov bought several iron foundries along with the villages belonging to them - Bobrovka, Elovka, Kujavoy. This was a large-scale purchase: Maltsov actually received all of Lyudinovo, surrounded by nearby villages. Thus, Pyotr Evdokimovich Demidov became the last owner of Lyudinovo in the Demidov family. There were rumors that this measure was forced: Demidov allegedly lost to Maltsov at cards and was forced to give him everything he owned.

It was at the Lyudinovsky plant that the very first Russian rails were produced in 1841. Shortly before this, Emperor Nicholas I ordered the construction of a railway named in his honor Nikolaevskaya (later it was renamed Oktyabrskaya). In 1858, three steamships were assembled at this plant - the first in the history of Russia, and ten years later the first open-hearth furnaces were launched.

In 1861, when the heavy burden of serfdom was lifted, Lyudinovo received a new status, becoming the center of the Lyudinovo volost of the Zhizdrinsky district of the Kaluga province.

Over the course of several centuries, Lyudinovo has undergone dramatic changes. The impetus for its development was the activity of Demidov: in the two centuries since his death, Lyudinovo from a village of three huts, lost among the impenetrable Bryansk forest, turned into a huge settlement for its time, numbering about 10,000 inhabitants.

The history of Lyudinov in the 20th century

At the beginning of the century, the industrial industry in Lyudinovo developed at a rapid pace. The success of the development of the region is evidenced by the essay “America in Russia” left by V. I. Nemirovich-Danchenko. The writer, who personally visited Lyudinovo, was not afraid to compare it with Sheffield, a major English industrial center. Enterprises are being reconstructed and locomotive production is expanding. In 1908, the Lyudinovo plant became the main plant of the domestic locomotive industry. After the reconstruction of the plant, new houses and living quarters began to be built. The houses were built mainly as apartments for factory workers, and schools for men and women were also built.

The successes of the locomotive industry were interrupted by the First World War that began in 1914. The number of workers dropped sharply, as did the number of locomotives produced at the plant. In 1917, the War Department ordered the plant to produce shells and ammunition for military needs.

The revolution of 1917 radically changed the external and internal appearance of Lyudinovo. In March, a Council of Workers' Deputies and a workers' militia were created here, responsible for protecting the plant. On November 9, 1917, Soviet power was established in Lyudinovo, and in June of the following year the Soviet government issued a decree on the nationalization of all large industry. The management of the enterprises almost immediately changed: Ivan Andreevich Volovshchikov now became the director of the plant. The economic situation of the plant after the revolution was deplorable: the plant workers received their own products as wages - frying pans, pots, etc.

Over time, the situation became worse: soon famine began in Lyudinovo. Lenin, by that time the head of the government, tried to somehow alleviate the situation of the Lyudinists, deciding to help them “within reasonable limits.” Help was provided in the following way: military food detachments were organized at the plant, which took away the “surplus” from the Kursk and Voronezh peasants. All these operations were carried out under the strict control of the Bolsheviks.

By 1923, the plant's position had stabilized: production of locomotives, radiators, and cast-iron cookware began again. The Lyudinists were dissatisfied with the Soviet government: the revolution was over, and they still received meager salaries. The government did not respond to the demand for rations and increased wages. As a result, labor unrest began in Lyudinovo, which lasted six months. But by the end of the twenties of the last century, the economic situation had improved significantly: porcelain products began to be produced at the plant, and active housing construction began throughout the region. Lyudinovo slowly but surely rose from the revolutionary ashes.

In 1929, Lyudinovo became the center of the Lyudinovo district of the Bryansk district of the Western region.

But harsh measures against church institutions loomed ahead. The Soviet regime was merciless towards religion: thousands of Russian churches and monasteries were closed and converted into barns, sports centers, even cinemas. Thousands of clerics were shot. Monks and nuns were resettled, church property was mercilessly liquidated. Not a single city escaped this fate. In 1929, it also befell Lyudinovo: a decree was issued to close the Kazan Church. From now on it was transferred to the Palace of Culture. The factory workers actively supported this decision, but in Lyudinovo there were many believers who went on strike against the closure of the temple. Their rejection was not limited to words: they were constantly on duty in the Church of the Kazan Mother of God, locking themselves there and refusing to give up the shrine. The local police did not dare to take extreme measures, and Latvian riflemen were sent to help them. Only then was the Kazan Temple captured. According to eyewitnesses, its closure was accompanied by blasphemous, outrageous behavior of the military: they tore into pieces and burned canvases, broke icons, remaining deaf to the pleas and cries of the believers who crowded in front of the temple in the hope of pardon. The repressions also did not spare Lyudinovo: more than ten clergy were shot, and the same number were sent into exile.

Against the background of unrest and confusion (manifestations characteristic of Soviet power), it is worth noting that 1938 was a big date for Lyudinovo. The workers' settlement has now officially received city status.

During the Great Patriotic War, the entire economy of Lyudinovo was put on a war footing from the very first day. The Lyudinites felt all the hardships of the war already by 1942, when a time of famine began in the city. Lyudinists showed themselves valiantly: many of the city residents were awarded the title of Hero of the Soviet Union, some (for example, Alexey Semenovich Shumantsov) received this award posthumously.

During the war years the industrial sector suffered the most. Restoration and construction work began in the first days after the end of the war. This process proceeded very quickly: Lyudinovo factories reached pre-war levels by 1947, i.e. in just two years.

In 1963, Lyudinovo became a city of regional subordination. In 1966, the first cosmonaut Yuri Gagarin arrived in Lyudinovo. Gagarin’s visit to the city was associated with his nomination as a deputy to the Council of Nationalities of the USSR Armed Forces. It was a great honor for the Ludynovites: they subsequently installed memorial plaques in honor of Gagarin’s visit. The boards still remain; one of them is on the factory building, the other is on the Palace of Culture.

The Chernobyl disaster was the first serious shock for Lyudinovo after the end of the Great Patriotic War. At the end of April 1986, along with heavy rains, radionuclides fell onto the territory of the Lyudinovo district. At that time, no one except specialists had any idea about the tragedy. People didn’t even realize that drinking water and air in Lyudinovo were dangerous not only to health, but also to life. Today, the content of radionuclides is much lower than the permissible norm.

In the early 1990s. In response to the economic crisis that swept across the country like an avalanche, food stamps and household goods appeared in Lyudinovo. The situation was so unstable that coupons in Lyudinovo were issued not only for butter, sugar and tobacco, but even for bread. Two years later, the coupons were abolished. The city's economy once again began to improve.

Lyudinovo also had its own museum, built in 1968 according to the design of the architect Sarkisov. Two years later the museum was open to the public.

Lyudinovo at present

Today Lyudinovo is an industrial city with its own infrastructure. All the financial and economic crises that the city faced in the last century have long passed. According to data for 2013, about 40,000 residents live in Lyudinovo. The region continues to develop in many directions - industrial, tourism, cultural. Lyudinovo is gradually gaining popularity in the tourism market: city guests are incredibly attracted to the natural resources of the region. For example, Lake Lompad is recognized as one of the seven wonders of the world in the Kaluga region. Perhaps this is why about one and a half thousand tourists come here every year. A significant advantage of the city is its panoramic view. Hundreds of illustrations serve as silent confirmation of the beauty of this city.

Among the main attractions of the city of Lyudinovo are the Church of St. Sergius of Radonezh, the Church of Paraskeva Pyatnitsa and the bell tower of the Trinity Church. All buildings were erected in the 19th century. The Temple of the Kazan Mother of God, closed during the Soviet period, has now again received the status of a church institution. It is now a functioning temple and is free to visit.

Despite its modest size, Lyudinovo is a city with a truly rich history, the origins of which date back to the pre-Petrine era. The history of Lyudinovo is the history of a remote village that once attracted major Russian industrialists with its rich natural resources and thereby secured its future. Over three centuries, the village grew into a city, the status of which it received in the second quarter of the twentieth century.

Nature

Lake Lompad, bordered along the banks by coniferous forest, is also called the Lyudinovo Reservoir due to its man-made origin. The Nepolot River originates from the lake. All these waters divide the city in two - into the eastern and western parts. Within the city limits, the width of the lake reaches one and a half kilometers.

Lake Lompad is one of the seven wonders of the Kaluga region[4].

From the west, the Bolva River approaches the city, flowing into the Desna near Bryansk. Almost repeating its bends, and in two places crossing the river, stretches the Vyazma-Kirov-Bryansk railway line passing through Lyudinovo.

The river network is widely developed both throughout the Kaluga region and in the Lyudinovsky district. The Bolva River belongs to the Dnieper basin, the Zhizdra River to the Volga basin. These are one of the largest rivers in the Kaluga region. All of them are characterized by a winding channel, a slight fall, and a slow flow.

On the southern side, the city includes the working village of Sukreml, which has its own Sukreml reservoir, formed by a dam on the river separating it from the water area of the upper lake.

Cities

Lyudinovo city

- a city in Russia, the administrative center of the Lyudinovsky district of the Kaluga region, forms an urban settlement. The population as of the end of 2011 is actually 41.2 thousand people. The city is located on the Nepolot River (Desna basin), 181 km from Kaluga. Lake Lompad, bordered along the banks by coniferous forest, is also called the Lyudinovo Reservoir due to its man-made origin. The Nepolot River originates from the lake. All these waters divide the city in two - into the eastern and western parts. Within the city limits, the width of the lake reaches one and a half kilometers. Lake Lompad is one of the seven wonders of the Kaluga region. From the west, the Bolva River approaches the city, flowing into the Desna near Bryansk. Almost repeating its bends, and in two places crossing the river, stretches the Vyazma-Kirov-Bryansk railway line passing through Lyudinovo. The river network is widely developed both throughout the Kaluga region and in the Lyudinovsky district. The Bolva River belongs to the Dnieper basin, the Zhizdra River to the Volga basin. These are one of the largest rivers in the Kaluga region. All of them are characterized by a winding channel, a slight fall, and a slow flow. On the southern side, the city includes the working village of Sukreml, which has its own Sukreml reservoir, formed by a dam on the river separating it from the waters of the upper lake. The area of the Lyudinovsky district is 930 km?, the territory of which is located in the center of the East European Plain, in the southwest of the Central Economic Region of the Non-Black Earth Zone of the Russian Federation. The territory lies on the ancient Precambrian Russian Platform, composed of crystalline rocks; traces of volcanic activity were also found. From above, the crystalline foundation is covered by a thick layer (about 1000 m) of sedimentary deposits of different ages. There are deposits of ceramic clays, sands, and phosphorites (Slobodo-Kotoretskoye in the Lyudinovsky and Duminichsky districts). The climate is temperate continental with distinct seasons (warm summers, moderately cold winters with stable snow cover). Local attractions: Church of St. Sergius of Radonezh (late 19th century), bell tower of the Trinity Church (1836), Church of Paraskeva Pyatnitsa (mid-19th century).

Education in the city of Lyudinovo

Institutions of additional education

Children's art school

259 students in 8 specialties, graduates - 39 people. in year

Children's music school

360 students in 11 specialties, graduates - 53 people. in year

Children's art school

175 students in 6 specialties, graduates - 36 people. in year

2 branches of a children's music school in the village of Voylovo and a children's art school in the village. Zarechny

Economy of the city of

Lyudinovo

Main industries: ferrous metallurgy (JSC "Krontif"), mechanical engineering (plants: diesel locomotive, aggregate (hydraulic and pneumatic equipment), mechanical engineering (machine tools, automated lines, hydraulic lifts). Factories: clothing, plastics. Food enterprises industry, timber industry enterprise. Deposits of ceramic clays, sands, phosphorites have been discovered in the area. Aggregatny Timber industry enterprise Machine-building plant Food industry enterprises Diesel locomotive-building plant Plastics factory Iron foundry Garment factory

History of the city of

Lyudinovo

Several centuries ago, on the banks of the Psur River there was a small village of Lyudinovo, lost among dense forests, consisting of several huts. Its inhabitants conquered patches of land from the forest, engaged in various crafts, arable farming, hunting, fishing, collecting honey from wild bees, and trading in fur, hemp, resin, and wax. For the first time, the village of Lyudinovo, Bryansk district, Botogovskaya volost, was mentioned in the “Scribe (census) books” for 1626, which included “5 peasant households, 2 bobyl households, 4 empty households,” surrounded by a palisade from the invasions of forest inhabitants, who were found here in abundance. Under Empress Catherine II, after Zhizdra became a district town on October 17, 1777, Lyudinovo, already as a village, was part of the Zhizdra district of the Kaluga governorship. On February 1, 1963, Lyudinovo was classified as a city of regional subordination. According to one version, the name of the city comes from the Old Russian name “Lyudin”, which means commoner - peasant craftsman, artisan. According to another version, from the phrase “New people.” Stele at the entrance to the city of Lyudinovo At the beginning of the 18th century, the Ural industrialist Evdokim Demidov built 2 dams on the Nepolot River and created an upper (Lyudinovo) and lower (Sukremlskoye) reservoir. In 1738, an iron foundry was founded on the Sukremlin reservoir. In 1745, an ironworks (now a diesel locomotive plant) was built on the Lyudinovo reservoir. In 1857-58, the plant produced the first military ships for the Black Sea Fleet and river vessels, and in 1879, the first freight steam locomotive in Russia was created. The greatest flourishing of industry occurred in 1875-85, when large government orders for steam locomotives and railroad cars were carried out in the city. In 1861, Lyudinovo became the center of the Lyudinovo volost of the Zhizdrinsky district of the Kaluga province. Since 1929, the city has been the center of the Lyudinovsky district of the Bryansk district of the Western region (since 1944 - the Kaluga region). In 1938, the working village of Lyudinovo was transformed into a city. During the Great Patriotic War it was occupied by Nazi troops and liberated on September 9, 1943. For two years the city was in the front line. During the occupation, an underground Komsomol group operated in Lyudinovo. In 1963, the city of Lyudinovo was classified as a city of regional subordination.

| Coat of arms of the city of Lyudinovo - In the azure field there is a concave narrow silver rafter, crowned with a cross of the same metal with radiance in the corners, burdened with a green mining vine and filled with scarlet, in which there is a golden inscribed narrow point, expanding in an arched manner at the base. The coat of arms of the city of Lyudinovo can be reproduced in two equally acceptable versions: - without the free part; - with a free part - a quadrangle, adjacent from the inside to the upper edge of the coat of arms of the city of Lyudinovo with the figures of the coat of arms of the Kaluga region reproduced in it. The version of the coat of arms with a free part is used after appropriate legislative confirmation of the procedure for including in the coats of arms of municipal formations of the Kaluga region a free part with the image of the coat of arms of the Kaluga region Coat of arms of the city of Lyudinovo in accordance with the Methodological recommendations for the development and use of official symbols of municipal formations (Section 2, Chapter VIII, paragraph. p. 45-46), approved by the Heraldic Council under the President of the Russian Federation on June 28, 2006, can be reproduced with a status crown of the established pattern. Rationale for symbolism: Lyudinovo was first mentioned in the Scribe books for 1626. Then it was a small village with several courtyards. The development of the village and its formation as a city is closely connected with the activities of the Russian industrialists the Demidovs. In 1732, Nikita Nikitovich Demidov came here to choose a place for the construction of a new ironworks. Two reservoirs were built here: the upper one - Lyudinovskoe and the lower one - Sukremlskoe. In 1738, an iron foundry was founded on the Sukremlin reservoir. In 1745, an iron-making plant (now a diesel locomotive plant) was built on the Lyudinovo Reservoir. In 1857-58. The plant produced the first military vessels for the Black Sea Fleet, river vessels, and in 1879 the first freight steam locomotive in Russia was created. The life of a modern city is also impossible to imagine without its industry. The mining vine placed in the city's coat of arms, borrowed from the Demidovs' coat of arms, as well as the allegorically depicted flow of molten metal symbolize the past and present of the city. The development of its city-forming enterprises from the ironworks to the modern Lyudinovsky diesel locomotive plant, the huge role of the Demidovs in the formation of city-forming enterprises. The vine is a symbol of research, knowledge, hidden resources. The symbolism of the silver rafter is multi-valued: - it allegorically symbolizes the location of the city on the watershed between the Oka and Dnieper water basins. - shows in a stylized manner the letter “L” - capital in the name of the city. The carved cross crowning the rafters symbolizes a unique landmark of the city - a crystal cross that has survived to this day from the iconostasis of the Church of the Kazan Icon of the Mother of God, created from crystal at the production of Russian industrialists Maltsov, who made a significant contribution to the development of Lyudinovo. Red color is a symbol of labor, courage, strength, beauty and celebration. The red color of the field is consonant with the work of workers in the engineering industry, which complements the content of the city’s coat of arms as an industrialized region. Gold is a symbol of wealth, stability, solar warmth and energy, respect and intelligence. Silver is a symbol of purity and perfection, peace and mutual understanding. Blue color is a symbol of honor, nobility, lofty aspirations, and spirituality. Green color is a symbol of youth, health, nature, and growth in life. The city is surrounded by forests, which has a beneficial effect on its ecology. Author group: idea of the coat of arms: Konstantin Mochenov (Khimki); artist and computer design: Oksana Afanasyeva (Moscow); rationale for symbolism: Kirill Perekhodenko (Konakovo). Approved by the decision of the City Duma of the urban settlement "City of Lyudinovo" (#255-r) dated November 28, 2008. | The flag of the city of Lyudinovo has not yet been approved, so it is not shown. |

Natural resources

The area of the Lyudinovsky district is 930 km², the territory of which is located in the center of the East European Plain, in the southwest of the Central Economic Region of the Non-Black Earth Zone of the Russian Federation. The territory lies on the ancient Precambrian Russian Platform, composed of crystalline rocks; traces of volcanic activity were also found. From above, the crystalline foundation is covered by a thick layer (about 1000 m) of sedimentary deposits of different ages.

There are deposits of ceramic clays, sands, and phosphorites (Slobodo-Kotoretskoye in the Lyudinovsky and Duminichsky districts).

The climate is temperate continental with distinct seasons (warm summers, moderately cold winters with stable snow cover).

Culture

Local attractions: Church of St. Sergius of Radonezh (late 19th century), bell tower of the Trinity Church (1836), Church of Paraskeva Pyatnitsa (mid-19th century).

Institutions of additional education

Children's art school

- 259 students in 8 specialties, graduates - 39 people. in year

Children's music school

- 360 students in 11 specialties, graduates - 53 people. in year

Children's art school

- 175 students in 6 specialties, graduates - 36 people. in year

2 branches of a children's music school in the village of Voylovo and a children's art school in the village. Zarechny

Cultural institutions of the city and region

Palace of Culture named after. Gogiberidze:

- number of amateur groups - 38,

- number of participants - 488 people.

District House of Culture

16 rural club institutions:

- 2200 seats,

- number of amateur art groups - 125,

- number of amateur performance participants - 1642 people.

Library system:

- 239 thousand copies, over 15.3 thousand readers

MU "Kinovideocenter":

- 9 film installations

Museum of Labor Glory:

- over 1.5 thousand visits per year

Temples Lyudinovo

- Temple of St. Sergius of Radonezh

- Temple in honor of the Holy Righteous Lazarus, Bishop of Kitia

- Temple of the Kazan Icon of the Mother of God

Our monuments are our heroes. City of Lyudinovo.

Memorial complex on Victory Square

In honor of the liberators, Victory Square was opened in the city in 1983. In the center of her composition is a warrior bugler announcing Victory. In memory of the victims, the Eternal Flame burns, and the names of the military units and units that liberated the city are immortalized.

Area of the complex: 8960 sq.m., covered with paving slabs. The approximate height of the stele is 30 m.

Walk of Fame

Memorial complex near Victory Square

1983 is the year the alley was created in honor of the 40th anniversary of the liberation of the Lyudinovsky district. The alley is lined with paving slabs, in its center there is a flower bed, on both sides of the Alley of Fame there are rectangular brick pedestals made of red brick with memorial plaques with busts of Heroes of the Soviet Union, natives of the Lyudinovo district, installed in a row. On both sides of the Alley there are slabs with the names of Lyudinists who died on the battlefields of the Great Patriotic War. Further in the center is a monument to underground heroes.

Monument to the heroes of the Komsomol youth underground

Installed in 1960 in the city park. To the left of the monument are images of underground heroes. The total length covering the monument with images of underground heroes is 10 meters.

City cemetery. Mass grave of underground workers

The mass grave is located in the city cemetery 30-35 meters to the left from the entrance to St. Lazarus Church. The monument was erected in 1968. On both sides of the burial mound there are two parallel rectangular steles made of light brown granite, mounted on a base of gray granite. On one of them in the left corner there is an image of the Star of the Hero of the Soviet Union and below the inscription: “A. Shumavtsov. 1925-1942". At a distance of 0.25 m from the top of the stele there is a square with a relief image of the face of Alexei Shumavtsov. On another stele there is an inscription carved: “A. Lyasotsky. 1925-1942". At a distance of 0.25 m from the top of the stele there is the same protruding square with a relief image of the face of Alexander Lyasotsky.

The grave contains the ashes of 2 underground fighters.

City cemetery. Mass grave

The burial took place in 1943. 135 soldiers were buried in the mass grave. A stylobate was built on a cement base, and on a pedestal there was a brick-lined and painted stele, the top of which was cut diagonally. At the top of the stele is a plaster bust of a soldier in a helmet with a cape behind his back. In the soldier's hands is a machine gun. The paving slabs around the stele with the bust are laid in such a way that they form a step leading to the architectural composition. At a distance of two slabs from the stele, flower beds are laid out to the left and right. Attached to the front side of the stele are two memorial plaques on which the names of the buried soldiers are engraved.

Tank

The monument was erected on September 9, 1973 to mark the 30th anniversary of the liberation of Lyudinovo. The T-34 tank No. 7992 is installed on a concrete pedestal at the entrance ring to the city from Zhizdra. On the left side of the pedestal are inscribed the words “Glory to the heroic liberators of the city. Your immortal feat will live in the hearts of grateful Lyudinists.”

Monument to Alexey Semenovich Shumavtsov, Hero of the Soviet Union

The monument, in which the name of the young leader of the Lyudinovo youth underground is forever imprinted, was erected in 1968 at the Lyudinovo-2 station, next to the railway station.

Sukremlin cemetery. Mass grave

The mass grave is located on the territory of the cemetery of the Sukreml microdistrict, surrounded by a metal fence, to the left of the Church of St. Sergius of Radonezh. It arose in 1943, when Soviet soldiers of the 1150th, 1313th, 1314th rifle regiments were buried here as a military unit; 912th Artillery Regiment; 66th Tank Regiment, who died in the battles for the liberation of Lyudinov, as well as Soviet soldiers who died of wounds in the 470th separate medical battalion. There is no burial mound. A monument was erected at the grave in 1959. On a concrete base, a plastered and painted rectangular pedestal is built of brick, on which a plaster sculptural group in the form of figures of a Red Army soldier and a sailor is installed. A Red Army soldier in a cap and cape holds a rifle with a bayonet-knife in his right hand, and with his left he leans on the shoulder of a kneeling sailor holding a tilted banner in his hands. Attached to the front side of the pedestal is a square metal plate, in the center of which is an image of a wreath intertwined with a ribbon, with the inscription inside: “Eternal glory to the heroes who fell in battles for the honor and freedom of our Motherland. 1943." Below is a memorial marble slab with the names of those buried carved on it. Around the monument, adjacent to it, there is a flower bed, behind which, along the perimeter of the monument, there is a path lined with cast iron tiles. Also around the monument there are bushes, behind which there is again a flower bed encircling the entire grave. All flower beds, paths and shrub plantings are bordered with border stones.

In total, the grave contains the ashes of 71 warriors.

Mass grave. St. F. Dzerzhinsky

The burial was carried out by local residents in 1943. Soviet soldiers of the 858th and 1150th rifle regiments were buried; 42nd Air Regiment, who died in the battles for the liberation of Lyudinov, as well as Soviet soldiers who died of wounds in the 122nd medical battalion and the 1157th field mobile hospital. In 1960, a monument was erected. The monument is a brick trapezoidal pedestal, with a granite slab attached to the base of the front edge. Carved on it are the words “Eternal glory to you, heroes” and below are the names of the buried soldiers. Between the columns of names there is an image of a five-pointed star. Above the slab there is a ledge on which is depicted a round wreath intertwined with a ribbon, in the middle of which there is a five-pointed star. At the top of the pedestal there is a plaster sculptural composition: the figure of a girl in a summer dress and headscarf, and a warrior with his head uncovered. The warrior’s left hand is lowered and clenched into a fist, and there is a machine gun on his shoulder. With his right hand he hugs the girl by the shoulder. The faces of the warrior and the girl are concentrated, tense, their gaze is directed into the distance. The approach to the monument is three-stage, paved with tiles. On the sides of the monument there are flower beds. Birch trees grow on the territory of the grave. The entire area of the grave is surrounded by a wooden picket fence. There are flower beds along the inner fence.

In total, the grave contains the ashes of 24 warriors.

Individual grave. St. P. Osipenko

The monument is erected on an earthen mound covered with turf. On a metal pedestal is a pyramidal metal obelisk with a flat top, topped with a five-pointed star. Attached to the obelisk is a metal plaque with the inscription: “Mikhalev Sergey Mikhailovich, b. 1917, died on January 9, 1942.” The burial was carried out by a military unit in 1943. The grave is located in the north-eastern part of the city, at the end of the street. P. Osipenko, at the edge of the forest.

Mass grave. St. M.E. Saltykova-Shchedrin

The burial took place in 1960. The monument is a rectangular reinforced concrete pedestal on which a plaster sculpture of a seated woman is installed on a stand in the form of a stone of indeterminate shape. With her right hand she holds the child, and with her left hand she lays a wreath. The woman's head is mournfully lowered. Attached to the front face of the pedestal is a black marble slab with the names of those buried carved on it. A path lined with paving slabs and bordered by curbstones leads to the pedestal. Linden and pine trees grow around the grave.

In total, the grave contains the ashes of 21 warriors.

Monument to members of partisan families shot in Lyudinovo

The monument was erected in 1957 near the Lyudinovo-1 station. A rectangular pedestal is built on a concrete stylobate, on which is installed a sculpture of a kneeling woman, mournfully bowing her uncovered head, holding a wreath with her right hand, and holding a scarf thrown over her shoulder with her left hand. The territory of the memorial site is surrounded by a metal fence, which is installed on a stone border. Bushes and trees grow on the territory of the memorial site.

Monument to Lyudinovo partisans

Installed in 2005 in the city center on III International Street. A rectangular pedestal is built on a concrete base of a black marble slab, with a curved five-pointed star made of granite stone at the top. On the sides there is an inscription: “To the Lyudinovo partisans.” At the top there is the inscription: “1941-1943”.

Monument at the site of the death of A. Shumavtsov and A. Lyasotsky, members of the Lyudinovo youth underground

1957 - a monument was erected on a marble slab covered with paving slabs. The monument consists of two parallel granite rectangular columns. Between them is a rectangular granite tablet with the inscription: “Here in November 1942, the heroes of the Komsomol, Lyudinists Alexey Shumavtsov and Alexander Lyasotsky were brutally tortured by the German fascists.” Below is a similar rectangular granite sign with the inscription: “Stop. Bow to their memory."

Monument to juvenile prisoners

The monument was erected in the Sukreml microdistrict in 2005 in the park near the district House of Culture. A memorial stone is installed on a concrete base, to which is attached a marble tablet with the inscription: “To minor prisoners of fascism. 1941-1945".

Monument to Home Front Workers

Installed in the city center in honor of the Lyudinovo workers, home front workers during the Great Patriotic War.

Monument in honor of fallen factory workers

The monument was erected in September 1973 to mark the 30th anniversary of the liberation of the Lyudinovsky district in the Sukreml microdistrict at the entrance of the Krontif Center JSC. A sculptural composition is installed on a concrete pedestal. On the right is the figure of a warrior with his right arm raised and bent. The left hand holds a wounded comrade leaning on the warrior’s exposed left knee. Nearby is a girl with her head down, the legs of a wounded warrior lying on her right knee. The composition is completely cast from cast iron. On both sides of the monument there are 6 memorial plaques with the names of the deceased factory workers. On the pedestal there is an inscription: “To the Sukreml iron foundries who died during the war of 1941-1945.”

Individual grave

The unknown soldier was buried in 1943. The grave is surrounded by a metal fence. On its territory there is a marble monument with the inscription: “Eternal memory to the heroes of the Great Patriotic War.” The grave is located to the right of Lyudinovo-1 station.

Literature:

- Book of Memory. T. XIV. - Kaluga: GRIF, 2007. - P. 608-626, 696.

To the list of monuments in Lyudinovsky district

People associated with the city

- Kireev, Grigory Petrovich

- Merenishchev, Nikolai Vladimirovich

- Savchenkov, Sergey Viktorovich

- Sveshnikov, Dmitry Konstantinovich

Heroes of the Soviet Union

- Visyashchev, Alexander Ivanovich

- Shumavtsov, Alexey Semenovich

- Svertilov, Alexey Ivanovich

- Vitin, Vladimir Karpovich

- Loktionov, Afanasy Ivanovich

- Chugunov, Ivan Yakovlevich

- Mitrokhov, Vasily Kuzmich

- Ignatkin, Fedor Semyonovich

- Utin, Alexander Vasilievich

- Volkov, Semyon Mikhailovich

- Belov, Alexey Ivanovich

Economy

Main industries: ferrous metallurgy (JSC "Krontif"), mechanical engineering (factories: diesel locomotive, aggregate (hydraulic and pneumatic equipment), mechanical engineering (machine tools, automated lines, hydraulic lifts), cable production (Lyudinovokabel plant)). . Factories: clothing, plastics. Food industry enterprises, timber industry enterprises. Deposits of ceramic clays, sands, and phosphorites have been discovered in the area.

- Aggregate plant

- — not working since mid-2014

- Lespromkhoz

- Machine-building plant

- Food industry enterprises

- Diesel Locomotive Plant – STM Group – Sinara

- Iron foundry

- Garment factory

- HozMart

- "Agro-Invest" - Greenhouse complex

Russian Prime Minister Dmitry Medvedev created a special industrial zone in Lyudinovo. He signed the corresponding resolution on December 31, 2012. According to it, the authorized capital of the special economic zone of industrial production type “Lyudinovo” will amount to 2.6 billion rubles[20].

Links

Settlements on Bolva (from source to mouth) Kaluga region Bolva |

Spas-Demensk

|

Novoaleksandrovsky

|

Verhulichi

|

Nagornoye

|

left tributary Kovylinka | left tributary Degna | left tributary Shrink | right tributary Pesochnya | Kirov

|

Pogost

|

Manino

|

right tributary Kolchinka | Lyudinovo

| left tributary Nepolot | Sukreml |Bryansk region right tributary Vereshchevka | Dyatkovo |

Lubokhna | Fokino

|

Šibenec | Raditsa-Krylovka | left tributary of the Raditz | Bryansk

(

Bezhitsa

)see further: Desna

An excerpt characterizing Lyudinovo

- Oh oh oh! - the girl howled, pointing to the outbuilding. “He’s the one, she’s the one who was our Vatera.” You burned, my treasure, Katechka, my beloved young lady, oh, oh! - Aniska howled at the sight of the fire, feeling the need to express her feelings. Pierre leaned towards the outbuilding, but the heat was so strong that he involuntarily described an arc around the outbuilding and found himself next to a large house, which was still burning only on one side of the roof and around which a crowd of French were swarming. Pierre at first did not understand what these French were doing, carrying something; but, seeing in front of him a Frenchman who was beating a peasant with a blunt cleaver, taking away his fox fur coat, Pierre vaguely understood that they were robbing here, but he had no time to dwell on this thought. The sound of the crackling and roar of collapsing walls and ceilings, the whistle and hiss of flames and the animated cries of the people, the sight of wavering, now scowling thick black, now soaring lightening clouds of smoke with sparkles and sometimes solid, sheaf-shaped, red, sometimes scaly golden flame moving along the walls , the sensation of heat and smoke and the speed of movement produced on Pierre their usual stimulating effect of fires. This effect was especially strong on Pierre, because Pierre suddenly, at the sight of this fire, felt freed from the thoughts that were weighing him down. He felt young, cheerful, agile and determined. He ran around the outbuilding from the side of the house and was about to run to the part of it that was still standing, when a cry of several voices was heard above his head, followed by the cracking and ringing of something heavy that fell next to him. Pierre looked around and saw the French in the windows of the house, who had thrown out a chest of drawers filled with some kind of metal things. Other French soldiers below approached the box. “Eh bien, qu'est ce qu'il veut celui la, [This one still needs something," one of the French shouted at Pierre. - Un enfant dans cette maison. N'avez vous pas vu un enfant? [The child is in this house. Have you seen the child?] - said Pierre. – Tiens, qu'est ce qu'il chante celui la? Va te promener, [What else is this interpreting? “Get to hell,” voices were heard, and one of the soldiers, apparently afraid that Pierre would take it into his head to take away the silver and bronze that were in the box, advanced threateningly towards him. - Un enfant? - the Frenchman shouted from above. – J'ai entendu piailler quelque chose au jardin. Peut etre c'est sou moutard au bonhomme. Faut etre humain, voyez vous... [Child? I heard something squeaking in the garden. Maybe it's his child. Well, it is necessary according to humanity. We are all people...] – Ou est il? Ou est il? [Where is he? Where is he?] asked Pierre. - Par ici! Par ici! [Here, here!] - the Frenchman shouted to him from the window, pointing to the garden that was behind the house. – Attendez, je vais descendre. [Wait, I’ll come down now.] And indeed, a minute later the Frenchman, a black-eyed fellow with some kind of spot on his cheek, in only his shirt, jumped out of the window of the lower floor and, slapping Pierre on the shoulder, ran with him into the garden. “Depechez vous, vous autres,” he shouted to his comrades, “commence a faire chaud.” [Hey, you're more lively, it's starting to get hot.] Running out behind the house onto a sand-strewn path, the Frenchman pulled Pierre's hand and pointed him towards the circle. Under the bench lay a three-year-old girl in a pink dress. – Voila votre moutard. “Ah, une petite, tant mieux,” said the Frenchman. - Au revoir, mon gros. Faut être humaine. Nous sommes tous mortels, voyez vous, [Here is your child. Ah, girl, so much the better. Goodbye, fat man. Well, it is necessary according to humanity. All people,] - and the Frenchman with a spot on his cheek ran back to his comrades. Pierre, gasping for joy, ran up to the girl and wanted to take her in his arms. But, seeing a stranger, the scrofulous, unpleasant-looking, scrofulous, mother-like girl screamed and ran away. Pierre, however, grabbed her and lifted her into his arms; she screamed in a desperately angry voice and with her small hands began to tear Pierre’s hands away from her and bite them with her snotty mouth. Pierre was overcome by a feeling of horror and disgust, similar to the one he experienced when touching some small animal. But he made an effort over himself so as not to abandon the child, and ran with him back to the big house. But it was no longer possible to go back the same way; the girl Aniska was no longer there, and Pierre, with a feeling of pity and disgust, hugging the painfully sobbing and wet girl as tenderly as possible, ran through the garden to look for another way out. When Pierre, having run around courtyards and alleys, came back with his burden to Gruzinsky’s garden, on the corner of Povarskaya, at first he did not recognize the place from which he had gone to fetch the child: it was so cluttered with people and belongings pulled out of houses. In addition to Russian families with their goods, fleeing here from the fire, there were also several French soldiers in various attire. Pierre did not pay attention to them. He was in a hurry to find the official’s family in order to give his daughter to his mother and go again to save someone else. It seemed to Pierre that he had a lot more to do and quickly. Inflamed from the heat and running around, Pierre at that moment felt even more strongly than before that feeling of youth, revival and determination that overwhelmed him as he ran to save the child. The girl now became quiet and, holding Pierre’s caftan with her hands, sat on his hand and, like a wild animal, looked around her. Pierre occasionally glanced at her and smiled slightly. It seemed to him that he saw something touchingly innocent and angelic in this frightened and painful face. Neither the official nor his wife were in their former place. Pierre walked quickly among the people, looking at the different faces that came his way. Involuntarily he noticed a Georgian or Armenian family, consisting of a handsome, very old man with an oriental face, dressed in a new covered sheepskin coat and new boots, an old woman of the same type and a young woman. This very young woman seemed to Pierre the perfection of oriental beauty, with her sharp, arched black eyebrows and a long, unusually tenderly ruddy and beautiful face without any expression. Among the scattered belongings, in the crowd in the square, she, in her rich satin cloak and a bright purple scarf covering her head, resembled a delicate greenhouse plant thrown out into the snow. She sat on a bundle somewhat behind the old woman and motionlessly looked at the ground with her large black elongated eyes with long eyelashes. Apparently, she knew her beauty and was afraid for it. This face struck Pierre, and in his haste, walking along the fence, he looked back at her several times. Having reached the fence and still not finding those he needed, Pierre stopped, looking around. The figure of Pierre with a child in his arms was now even more remarkable than before, and several Russian men and women gathered around him. – Or lost someone, dear man? Are you one of the nobles yourself, or what? Whose child is it? - they asked him. Pierre answered that the child belonged to a woman in a black cloak, who was sitting with the children in this place, and asked if anyone knew her and where she had gone. “It must be the Anferovs,” said the old deacon, turning to the pockmarked woman. “Lord have mercy, Lord have mercy,” he added in his usual bass voice. - Where are the Anferovs! - said the woman. – The Anferovs left in the morning. And these are either the Marya Nikolaevnas or the Ivanovs. “He says she’s a woman, but Marya Nikolaevna is a lady,” said the yard man. “Yes, you know her, long teeth, thin,” said Pierre. - And there is Marya Nikolaevna. “They went into the garden, when these wolves swooped in,” the woman said, pointing at the French soldiers. “Oh, Lord have mercy,” the deacon added again. - You go over there, they are there. She is. “I kept getting upset and crying,” the woman said again. - She is. Here it is. But Pierre did not listen to the woman. For several seconds now, without taking his eyes off, he looked at what was happening a few steps away from him. He looked at the Armenian family and two French soldiers who approached the Armenians. One of these soldiers, a small, fidgety man, was dressed in a blue overcoat belted with a rope. He had a cap on his head and his feet were bare. The other, who especially struck Pierre, was a long, stooped, blond, thin man with slow movements and an idiotic expression on his face. This one was dressed in a frieze hood, blue trousers and large torn boots. A little Frenchman, without boots, in a blue hiss, approached the Armenians, immediately, saying something, took hold of the old man’s legs, and the old man immediately began hastily to take off his boots. The other, in a hood, stopped opposite the beautiful Armenian woman and silently, motionless, holding his hands in his pockets, looked at her. “Take, take the child,” said Pierre, handing over the girl and addressing the woman imperiously and hastily. - Give it to them, give it to them! - he shouted almost at the woman, putting the screaming girl on the ground, and again looked back at the French and the Armenian family. The old man was already sitting barefoot. The little Frenchman took off his last boot and clapped the boots one against the other. The old man, sobbing, said something, but Pierre only caught a glimpse of it; all his attention was turned to the Frenchman in the hood, who at that time, slowly swaying, moved towards the young woman and, taking his hands out of his pockets, grabbed her neck. The beautiful Armenian woman continued to sit in the same motionless position, with her long eyelashes lowered, and as if she did not see or feel what the soldier was doing to her. While Pierre ran the few steps that separated him from the French, a long marauder in a hood was already tearing the necklace she was wearing from the Armenian woman’s neck, and the young woman, clutching her neck with her hands, screamed in a shrill voice. – Laissez cette femme! [Leave this woman!] - Pierre croaked in a frantic voice, grabbing the long, hunched soldier by the shoulders and throwing him away. The soldier fell, got up and ran away. But his comrade, throwing away his boots, took out a cleaver and menacingly advanced on Pierre. - Voyons, pas de betises! [Oh well! Don’t be stupid!] – he shouted. Pierre was in that rapture of rage in which he remembered nothing and in which his strength increased tenfold. He rushed at the barefoot Frenchman and, before he could take out his cleaver, he had already knocked him down and was hammering at him with his fists. An approving cry from the surrounding crowd was heard, and at the same time a mounted patrol of French lancers appeared around the corner. The lancers trotted up to Pierre and the Frenchman and surrounded them. Pierre did not remember anything of what happened next. He remembered that he had beaten someone, he had been beaten, and that in the end he felt that his hands were tied, that a crowd of French soldiers was standing around him and searching his dress. “Il a un poignard, lieutenant, [Lieutenant, he has a dagger,”] were the first words that Pierre understood. - Ah, une arme! [Ah, weapons!] - said the officer and turned to the barefoot soldier who was taken with Pierre. “C’est bon, vous direz tout cela au conseil de guerre, [Okay, okay, you’ll tell everything at the trial,” said the officer. And after that he turned to Pierre: “Parlez vous francais vous?” [Do you speak French?] Pierre looked around him with bloodshot eyes and did not answer. His face probably seemed very scary, because the officer said something in a whisper, and four more lancers separated from the team and stood on both sides of Pierre. – Parlez vous francais? – the officer repeated the question to him, staying away from him. – Faites venir l'interprete. [Call an interpreter.] – A small man in a Russian civilian dress emerged from behind the rows. Pierre, by his attire and speech, immediately recognized him as a Frenchman from one of the Moscow shops. “Il n'a pas l'air d'un homme du peuple, [He doesn't look like a commoner," the translator said, looking at Pierre. – Oh, oh! ca m'a bien l'air d'un des incendiaires,” the officer blurted out. – Demandez lui ce qu'il est? [Oh, oh! he looks a lot like an arsonist. Ask him who he is?] he added. - Who are you? – asked the translator. “The authorities must answer,” he said. – Je ne vous dirai pas qui je suis. Je suis votre prisonnier. Emmenez moi, [I won't tell you who I am. I am your prisoner. Take me away,” Pierre suddenly said in French. - Ah, Ah! – the officer said, frowning. - Marchons! [A! A! Well, march!] A crowd gathered around the lancers. Closest to Pierre stood a pockmarked woman with a girl; When the detour started moving, she moved forward. -Where are they taking you, my darling? - she said. - This girl, what am I going to do with this girl, if she’s not theirs! - the woman said. – Qu'est ce qu'elle veut cette femme? [What does she want?] - asked the officer. Pierre looked like he was drunk. His ecstatic state intensified even more at the sight of the girl he had saved. – Ce qu'elle dit? - he said. “Elle m'apporte ma fille que je viens de sauver des flammes,” he said. - Adieu! [What does she want? She is carrying my daughter, whom I saved from the fire. Farewell!] - and he, not knowing how this aimless lie escaped him, walked with a decisive, solemn step among the French. The French patrol was one of those that were sent by order of Duronel to various streets of Moscow to suppress looting and especially to capture the arsonists, who, according to the general opinion that emerged that day among the French of the highest ranks, were the cause of the fires. Having traveled around several streets, the patrol picked up five more suspicious Russians, one shopkeeper, two seminarians, a peasant and a servant, and several looters. But of all the suspicious people, Pierre seemed the most suspicious of all. When they were all brought to spend the night in a large house on Zubovsky Val, in which a guardhouse was established, Pierre was placed separately under strict guard. In St. Petersburg at this time, in the highest circles, with greater fervor than ever, there was a complex struggle between the parties of Rumyantsev, the French, Maria Feodorovna, the Tsarevich and others, drowned out, as always, by the trumpeting of the court drones. But calm, luxurious, concerned only with ghosts, reflections of life, St. Petersburg life went on as before; and because of the course of this life, it was necessary to make great efforts to recognize the danger and the difficult situation in which the Russian people found themselves. There were the same exits, balls, the same French theater, the same interests of the courts, the same interests of service and intrigue. Only in the highest circles were efforts made to recall the difficulty of the present situation. It was told in whispers how the two empresses acted opposite to each other in such difficult circumstances. Empress Maria Feodorovna, concerned about the welfare of the charitable and educational institutions under her jurisdiction, made an order to send all institutions to Kazan, and the things of these institutions were already packed. Empress Elizaveta Alekseevna, when asked what orders she wanted to make, with her characteristic Russian patriotism, deigned to answer that she could not make orders about state institutions, since this concerned the sovereign; about the same thing that personally depends on her, she deigned to say that she will be the last to leave St. Petersburg.

The city of Lyudinovo is the administrative center of the Lyudinovo district of the Kaluga region. It is located 188 kilometers southwest of Kaluga and 70 kilometers northeast of Bryansk on the banks of a picturesque lake and river under the same name Lompad .

The population of the city is 41,127 people.

The name of the city comes from the Old Russian name “Lyudin”, which means commoner - peasant craftsman, artisan.

Back in 1626, on the banks of the Psur River there was a small village of Lyudinovo, lost among dense forests, consisting of several huts. It was at this time that the village of Lyudinovo, Bryansk district, Botogovskaya volost, was first mentioned in the “Scribe (census) books.” Then it consisted of “5 peasant households, 2 bobyl households, 4 empty households,” surrounded by a palisade from the invasions of forest inhabitants, who were found here in abundance.

Its inhabitants conquered patches of land from the forest, engaged in various crafts, arable farming, hunting, fishing, collecting honey from wild bees, and trading in fur, hemp, resin, and wax.

Nikita Nikitovich Demidov founded metallurgical production here. In 1745, the first blast furnace was launched at the Lyudinovo plant.

Under Empress Catherine II , after Zhizdra became a district town on October 17, 1777, Lyudinovo, already as a village, was part of the Zhizdra district of the Kaluga governorship.

Significant successes in the factory business were achieved during the period of ownership of the Lyudinovo factories by the major Russian industrialist S.I. Maltsov. Through his efforts, mechanical engineering began to develop in Lyudinovo. They produce steam engines, steamships, engines for sea vessels, freight steam locomotives, locomotives... Steamboats manufactured in Lyudinovo sailed along the Dnieper and Volga. The most famous of them are the passenger steamer “Lastochka” and the cargo-passenger “John the Theologian”. Their captains were people from Lyudinov. Many small steam ships sailed on Bolva and Lake Lompad . The first Russian steam engine, the first rails for the Moscow-Petersburg railway, the first freight locomotive and much more were manufactured at the Lyudinovsky plant. Lyudinovo craftsmen were famous for their art of furnace casting, enamel production, and various household items.

The city grew and developed along with the factories. By the end of the 19th century, there were more than 10 thousand inhabitants Lyudinovo

In 1861, Lyudinovo became the center of the Lyudinovo volost of the Zhizdrinsky district of the Kaluga province.

In 1885, Lyudinovo . In a letter from Lyudinovo, he reported: “I... am in Lyudinovo, there are a lot of plants and factories, and an iron foundry. We just spent the whole evening walking around the factory where they cast iron and make iron. All this is very amazing, terrible work and most necessary.”

Since the second half of the 19th century, Lyudinovo has been one of the centers of the labor movement.

Since 1929, the city has been the center of the Lyudinovsky district of the Bryansk district of the Western region (since 1944 - the Kaluga region).

In 1938, the working village of Lyudinovo was transformed into a city.

The Great Patriotic War became a severe test for Lyudinists. On October 4, 1941, the city was occupied by the Nazis. The front line ran through the area. Stubborn, bloody battles raged for two years.

On September 9, 1943, the city was liberated from the fascist invaders. In honor of the liberators, Victory Square was opened in the city in 1983. In the center of her composition is a warrior-bugler announcing Victory. In memory of the victims, the Eternal Flame burns, and the names of the military units and units that liberated the city are immortalized.

After liberation, work began to restore the city and its industrial enterprises. The power plant started working, and after some time the foundries produced their first melt. Production of products for the front began in Lyudinovo By 1947, factories had reached pre-war levels.

Since 1958, diesel locomotive construction has been developing in Lyudinovo . A significant step in the development of diesel locomotive construction was the development of production of diesel locomotives TEM7 and TEM7A. The production of other railway equipment has been mastered - diesel trains, traction and power plants, snow plows, railcars, etc.

On February 1, 1963, Lyudinovo was classified as a city of regional subordination.

A new stage in the development of the city was the appearance of two more large industrial enterprises in Lyudinovo - aggregate and machine-building plants. The production of power hydraulics and hydraulic equipment was established, metalworking machines with numerical control, automatic lines for automotive industry enterprises, and consumer goods were produced. Currently, these enterprises produce hydraulic equipment for the mining industry, railway equipment, hydraulic lifts and much more.

In 2006, the district received the status of a municipal district, the city of Lyudinovo became part of the district as an urban settlement.

The youngest enterprise is CJSC, which produces cable products for a wide variety of purposes.

Today the city has a developed infrastructure, a modern network of energy, gas and transport communications.

Lake Lompad , bordered along the banks by a coniferous forest, is also called the Lyudinovo Reservoir due to its man-made origin. The Nepolot River originates from the lake . All these waters divide the city in two into the eastern and western parts. Within the city limits, the width of the lake reaches one and a half kilometers.

Bolva River, which flows into the Desna near Bryansk, approaches the city from the west. Almost repeating its bends, and in two places crossing the river, stretches the Vyazma-Kirov-Bryansk railway line Lyudinovo

On the southern side, the city includes the working village of Sukreml, which has its own reservoir, the Sukreml reservoir , formed by a dam on the river separating it from the water area of the upper lake.

In 1960, a monument to the heroes of the Lyudinovo underground was unveiled in the city. 11 Lyudinovo members became Heroes of the Soviet Union during the war. In places of battles, on the mass graves of soldiers, monuments and memorial plaques were erected.

Some of the attractions in the area include:

Natural:

Natural monument “Lake Lompad”

Natural monument “Kaluganovo Meadow”

Natural monument "Molevskoe"

Historical and cultural:

Church of Sergius of Radonezh (late 19th century),

Bell tower of Trinity Church (1836),

Church of Paraskeva Pyatnitsa (mid-19th century).

Chapel in honor of the icon of the Mother of God “Burning Bush” on the territory of the OPSS Main Directorate of the Ministry of Emergency Situations

People's Museum of the History of Lyudinovo Diesel Locomotive Plant

Home Front Workers' Square

Memorial Square for Young Prisoners

Square in memory of Lyudinovo partisans

Phone code: +7 48444 City website: www.lyudinovo.org