This term has other meanings, see Semiluki (meanings).

| City Semiluki Flag | Coat of arms |

| A country | Russia, Russia |

| Subject of the federation | Voronezh regionVoronezh region |

| Municipal district | Semiluksky |

| urban settlement | Semiluki |

| Coordinates | 51°41′00″ n. w. 39°02′00″ E. long / 51.68333° north w. 39.03333° E. d. / 51.68333; 39.03333 (G) [www.openstreetmap.org/?mlat=51.68333&mlon=39.03333&zoom=12 (O)] (Z)Coordinates: 51°41′00″ N. w. 39°02′00″ E. long / 51.68333° north w. 39.03333° E. d. / 51.68333; 39.03333 (G) [www.openstreetmap.org/?mlat=51.68333&mlon=39.03333&zoom=12 (O)] (I) |

| Based | in 1615 |

| City with | 1954 |

| Square | 14[1]km² |

| Center height | 130 |

| Population | ↗26,721[2] people (2016) |

| Density | 1908.64 people/km² |

| National composition | Russians |

| Confessional composition | Orthodox |

| Names of residents | Semiluktsy, Semiluktsy |

| Timezone | UTC+3 |

| Telephone code | +7 47372 |

| Vehicle code | 36, 136 |

| OKATO code | [classif.spb.ru/classificators/view/okt.php?st=A&kr=1&kod=20249501000 20 249 501 000] |

| Official site | [semiluki-gorod.ru/i-gorod.ru] |

| Semiluki Moscow |

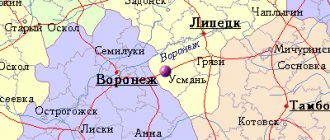

| Voronezh Semiluki |

Audio, photo and video

on Wikimedia Commons

K:Settlements founded in 1615

Semiluki

- a city (since 1954[3]) in Russia, the administrative center of the Semiluki district of the Voronezh region and the urban settlement of Semiluki.

Population - 26,721[2] people. (2016).

By Order of the Government of the Russian Federation dated July 29, 2014 No. 1398-r “On approval of the list of single-industry towns”, the municipal formation is included in the category “Single-industry municipal formations of the Russian Federation (single-industry towns), in which there are risks of deterioration of the socio-economic situation”[4].

Story

In 1894, during the construction of the Voronezh - Kursk railway, a small stop appeared here, named after the nearby village of Semiluki. At that time there was only one building here - the house of the trackman. And on September 1, 1926, construction began. This is how a new settlement was born - the working village of Semiluki, which was formed in 1929.

Places near the city are rich in archaeological sites. The first information about archaeological monuments on the territory of the Semiluksky district dates back to the 17th century[5].

In the 1930s, the Semiluksky section of the Don River was examined by employees of the Voronezh Museum of Local Lore, as a result of which they discovered the Semiluksky settlement.

In 1954-1956, archaeological exploration was carried out within the Semiluksky region by the Verkhnedonsky expedition of the Institute of Academy of Sciences of the USSR under the leadership of P. D. Liberov[5]. Among the significant number of identified monuments, three settlements on the right bank of the Don in the vicinity of the village of Semiluki, dating back to the 17th-18th centuries, should be noted.

In 1965, exploration along the Veduga River was carried out by an expedition of Voronezh State University under the leadership of A.D. Pryakhin. In 1985, the lower reaches of the Veduga River were explored by A. S. Savrasov. In 1985, the area was surveyed by Yu. D. Razuvaev. On the territory of the village of Semiluki, he discovered 2 settlements, monitoring of which was carried out by the author in 2006. In 1999, Yu. D. Razuvaev conducted excavations of the fortification line of this settlement[5].

In 2006, archaeologist A. N. Golotvin carried out archaeological exploration along the right bank of the Don from the highway bridge across the Don in the area of the city of Semiluki to the confluence of the Don Veduga. The settlement of Chernyshova Gora I was discovered. From the settlement, ceramics of the Voronezh and Catacomb cultures of the Bronze Age (1st half of the 2nd millennium BC), Borshchev culture (X - 1st half of the 11th century), Old Russian time (XIII-XIV centuries)[5]. The settlements revealed materials from the Chalcolithic era (Repen culture), Bronze Age (Voronezh, Catacomb, Abashevo, Srubnaya cultures), Early Iron Age (Scythoid, such as the Kashirki-Sedelok monuments), and Old Russian times.

Some historians of the Voronezh region associate the archaeological site with the chronicle settlement of Usugruv (translated from Turkic Us

- river,

Ugrov

- ditch, mountain), which meant a settlement near the river on a high mountain[6].

The Russian name of this settlement was, apparently, Ogiben

(as the monastery was later called). There are also attempts in science to connect the Semilukskoe settlement with the chronicle city on the Don.

In 1111, Prince Vladimir Monomakh approached the city on the Don, and since it was captured by the Polovtsians, he set it on fire. The campaigns of the Russian princes in 1111 and 1116 in these regions drove the Polovtsy from these places[6].

A.V. Kruzhilov. History of the Voronezh village of Semiluki (competition “Heritage of Ancestors to the Young”)

The relevance of the topic of this study is due to the need to form patriotism, which is the unifying idea of the Russian nation. Instilling patriotism in the younger generation begins with a respectful attitude towards the history of our country and love for their small homeland.

The history of my native village of Semiluki is inextricably linked with the history of the Russian people and the Russian state. It arose with the formation of the ancient Russian state, existed during the period of appanage Rus' and the Mongol-Tatar yoke, the formation of a centralized state and the Russian Empire. The village residents lived through the revolutionary events of 1917, took part in the construction of socialism, and fought against the Nazi invaders during the Great Patriotic War. After the Great Victory over fascism, they restored the destroyed economy and worked for the good of the Motherland and the people. The purpose of the study is to summarize historical information about the emergence and development of the village of Semiluki.

During the period of Kievan Rus (in the first quarter of the 12th century), an ancient Russian settlement arose on the site of the modern village of Semiluki, the population of which was engaged in agriculture, beekeeping, and fishing. In the area of the village, a crossing was established across the Don on the trade route “from Bolgar to Kyiv.” In 1389, the newly elected Moscow Metropolitan Pimen sailed along the Don. On the territory of the settlement, he met with the Yelets prince Yuri, the borders of whose possessions passed through this territory [1]. For a long time it was unknown where exactly this meeting took place. The answer was received in May 1911, when a landslide occurred in one of the Semiluki peasant households. As a result of the collapse of the earth, at a depth of 3 meters, a vaulted corridor with a semicircular arch was discovered, to the west of it - a passage one and a half meters long, intersecting with a third corridor. The northern passage led to a quadrangular room with a straight ceiling as high as a man. The walls, floor, ceiling and vaults were covered with clay. There were no traces of human activity in the cave, except for cracked clay four-pointed crosses on the ceiling of the room [2].

An important historical find at the turn of the 19th – 20th centuries. On the territory of the village there are treasures of Tatar coins, among which was the Novgorod half in the form of a silver ingot with the inscription “Andko” and customs signs of Russian princes, in particular with the inscription “Prince Vsevolod”. It is known that the Central Asian conqueror the Great Tamerlane was in these places after his victory over Tokhtamysh, khan of the Golden Horde. In 1395, Tamerlane's troops destroyed all settlements on the Don, including Semiluksk.

The revival of the village is associated with the founding of the city of Voronezh in 1585. A Cossack village arose on the territory of the village, which gradually grew into a village. It was founded by regimental Voronezh Cossacks, who carried out sentinel service to protect the southern borders of the Moscow State from attacks by the Crimean and Nogai Tatars. The patrol book of 1615, containing a description of the Voronezh fortress, mentions the Semiluki tract, near which additional (additional) land was given to the Voronezh Cossacks. In 1615, there were 22 households in Semiluki [3]. The Semiluk Cossacks belonged to the category of service people according to the device, who, unlike service people in the fatherland, did not inherit their rank and basically jointly owned the land allocated to them by the tsar for performing military service.

The appearance of the name “Semiluki” is associated with the bends (turns) of the Don River near the location of the village. The Watch Book says that the land was given to the Cossacks “at seven bows,” that is, at seven bends. On the other hand, the interpretation of the toponym “Semiluki” may be associated with the “seventh bow” - the seventh landmark on the Don River along the downward movement, on which a Cossack settlement was formed [4].

In 1620, at the request of local Cossacks, the Spaso-Preobrazhensky Monastery was founded near Semiluki on the slope of a high mountain. All the buildings of the monastery were wooden. At its foundation, the monastery received the status of “sick leave”, because “poloneniks (prisoners) are tonsured when they come out of captivity and are crippled” [5]. Being a kind of home for the disabled, the monastery, naturally, was maintained at the expense of the local population, for the protection of which disabled monks did not spare their lives, carrying out sentry duty.

The monastery had its own property: 60 acres of land, meadows, a vegetable garden, an apple orchard, a forest, and a water mill. On the banks of the Don, the monks grew hemp and cabbage. The monastery received income from the crossing of the Don, as well as from the annual fair on the eleventh day after Easter.

On May 15, 1697, the Spaso-Preobrazhensky Monastery partially fell into the ground, the wooden church in the name of the holy martyr Paraskeva Pyatnitsa settled, and its walls began to crack. The monastery was moved to a new location. In 1724, the bell tower that was built gave a certain slope and seemed to be falling, like the Leaning Tower of Pisa. The monks did not even suspect the existence of underground voids under the village. By order of Bishop Tikhon of Voronezh and Yelets, the monastery was abolished in 1769. The stone church in honor of the Transfiguration of the Lord, built to replace the wooden one, was converted into the parish church of the village of Semiluki [6].

The majority of the population in the first half of the 18th century in the village of Semiluki were odnodvortsy - descendants of service people (Cossacks, archers, gunners and soldiers). They were personally free, but many of them were not owners of cultivated lands. In the 19th century, odnodvortsy became part of the state peasants. Historical memory contributed to the formation of such personal qualities among village residents as hard work, courage and independence of judgment. The main occupations of the population were arable farming, agriculture and forestry. Development of the village in the XVIII-XIX centuries. The proximity to the settlement of Endovishche and the road leading from the city of Voronezh to the district town of Zemlyansk contributed to this. There was a fair in Semiluki, which attracted traders, artisans and peasants from all over the area.

The Semilukians cultivated the lands beyond the Don and Voronezh rivers. They used the site, located near the mouth of the Voronezh River, as a hayfield where they kept cattle in the summer. To have shelter while grazing livestock, they built houses next to the land. On the map of the Voronezh governorship of 1780, a small farm was marked at this place. In 1859 there were only 8 courtyards on the farm. But in the second half of the 19th century, the farm began to expand due to new settlers. The name Semilukskie Vyselki was assigned to the farmstead, since it was started by settlers from the village of Semiluki [4].

Semiluki residents took part in the Patriotic War of 1812. 9 recruits were sent from the Church of the Transfiguration to the battle with the French. In June 1878, the revolutionary populist M.R. Popov lived in the village for some time and was looking for a place for communal settlements. At this time, in Semiluki there were 147 households and 1026 inhabitants (among them 38 men and 3 women were literate). In communal use there were 2053 acres of arable land, 206 acres of hay land and 222 acres of pasture. In total there were 383 horses, 270 cows, 996 sheep and 215 pigs; 18 households had no livestock, 24 households were horseless, 62 families were engaged in fishing. In subsequent years, Semiluki continued to develop. In 1900, the village had 161 courtyards, 1096 residents, zemstvo and parish schools, a steam mill, 2 tea shops, a tavern and 7 handicraft establishments. By the beginning of 1917, 1,115 people lived in the village of Semiluki [1].

After the October Revolution of 1917, Soviet power in the village was established at the end of December 1917. In the summer of 1919, the village was occupied by Denikin's troops and was subjected to looting by the White Cossacks. In September, the White Guards were driven out as a result of the Voronezh-Kastornensky operation of the Red Army [3]. In 1923, the Voronezh Agricultural Institute (currently the Voronezh State Agrarian University named after Peter the Great) took patronage over the village, organizing a reading room and a library in Semiluki. In 1926, the village had: 261 courtyards, 1,505 residents, a school, a reading hut. On July 17, 1928, the collective farm “Red Plowman” was organized on the territory of the village. In 1930, the collective farm was visited by the chairman of the Central Executive Committee of the USSR, the “all-union headman” Kalinin M.I., who held a meeting of activists of the collective farm movement. In 1932-1933 the village suffered from famine.

When the Voronezh region was formed in 1934, the center of the Semiluki district became the village of Semiluki, formed in 1894 at the railway station located next to the village of Semiluki. The village was also named “Semiluki”. In 1954, the railway village was transformed into the city of Semiluki. But the village of Semiluki survived and continued its history.

After the start of the Great Patriotic War, 1,246 people left the village to fight the Nazis [7]. The war directly affected Semiluki in July 1942, when the offensive of Wehrmacht units began in the direction of the city of Voronezh according to the Operation Blau plan. The German troops near the villages of Semiluki and Endovishche were opposed by the 3rd battalion of the 605th Infantry Regiment, commanded by Senior Lieutenant A.M. Ushakov. However, having suffered heavy losses, the battalion was forced to retreat. The village was captured by the advancing forces of the 1st Infantry Regiment of the Grossdeutschland Motorized Division [8].

The occupation of the village of Semiluki lasted almost 200 days. The village council building housed the headquarters of the 7th Army Corps with a counterintelligence department and a propaganda sector [3]. There was a rural crossing across the Don River, which German troops used as a springboard for transferring their forces to Voronezh. The bridgehead was subject to Soviet air raids. During the 7 months they were in the village, the occupiers did not leave any livestock, buildings, or seeds.

During the occupation of the village by the Germans, Praskovya Ivanovna Shchegoleva accomplished a feat. At the cost of her life and the lives of her children, she saved the pilot of the downed Soviet Il-2 attack aircraft from death.

On September 15, 1942, Praskovya Shchegoleva, together with her young children, nephew and elderly mother, dug up potatoes in their own garden. Suddenly, a Soviet plane appeared over the hill on the outskirts of the village, sharply descending. A few moments later the plane crashed in the Shchegolevs’ garden. Praskovya and her relatives ran up to the burning attack aircraft, threw earth at it and helped the wounded pilot get out of the cockpit. Shchegoleva immediately sent the children to get men's civilian clothes, and she quickly explained to the pilot how to leave the village unnoticed.

As soon as the pilot disappeared, the Nazis drove up to Praskovya’s house in a car. When the Germans began to ask Praskovya where the pilot was, she answered in monosyllables: “I don’t know, I haven’t seen it.” For this, the Germans beat her eldest 12-year-old son Sasha and locked him in a barn, threatening to burn him alive. But this did not help break Praskovya. Then the Germans began to poison young children and Shchegoleva’s old mother with shepherd dogs. This also had no effect. The brutal fascists set the shepherd dogs on Praskovya’s children, and then killed her too. Together with Praskovya Shchegoleva, her four young children died, the youngest of whom was 2 years old, a 5-year-old nephew and a 72-year-old mother.

The pilot of the 825th assault aviation regiment of the 225th aviation division of the 2nd Air Army, Mikhail Tikhonovich Maltsev, who was rescued by Shchegolevoy, actually managed to get out of the village, but was unable to cross the Don. He decided to take refuge in one of the abandoned houses, and at night get a boat and try to leave the next day, but was betrayed to the Germans by one of the local residents who noticed him. Maltsev ended up in German captivity, but remained alive.

At the opening of the monument to Shchegoleva on May 9, 1965, M.T. Maltsev came to the village. In 1965, by Decree of the Presidium of the Supreme Soviet of the USSR, P.I. Shchegolev. was posthumously awarded the Order of the Patriotic War, 1st degree.

The liberation of the village of Semiluki took place on January 25, 1943 during the Voronezh-Kastornensky operation of the Red Army. The village was in a state of ruin, people lived in the surviving basements and cellars. Residents took part in the restoration of the collective farm, as well as the refractory plant located in the city of Semiluki, for which many were awarded medals “For Valiant Labor in the Great Patriotic War.” Only in 1949 did the level of agricultural development reach pre-war levels.

In 1962, G.A. Sklyarov was elected chairman of the Semiluksky collective farm. The village residents associate his name with an entire era of victories and achievements. The collective farm became a millionaire, for several years was a participant in the Exhibition of Economic Achievements of the USSR, and was awarded two gold medals. More than 200 collective farmers took part in the exhibition, 50 of them were awarded medals. In 1969, at the expense of the collective farm, an obelisk was built for 815 villagers who did not return from the war, and a new rural school was built. Until the dissolution of the Semiluksky collective farm in the 1990s, villagers worked on collective farms, fields and workshops. All residents were provided with work.

Currently, the village of Semiluki is the administrative center of the Semiluki rural settlement, which includes the villages of Semiluki and Endovishche. The settlement is located in the Semiluksky municipal district of the Voronezh region. On the territory of a rural settlement there are local government bodies, which are represented by the Council of People's Deputies, the head of the rural settlement, the administration of the rural settlement, control and accounting and election commissions. The head of the rural settlement is S.A. Shedogubov. The population of the village, including the population of the village of Endovishche, is 4380 people. Agricultural land (in thousands of hectares) is 4.942, including: arable land - 3.528, hayfields - 0.005, pastures - 0.536 thousand hectares. Forest fund lands – 2.1. Availability of livestock in personal farmsteads: cattle - 201, pigs - 112, poultry - 3350, horses - 6. As of 2022, the Semiluksky rural settlement has: a rural school, 2 first aid stations, an outpatient clinic, Semiluksky and Endovishchensky rural cultural palaces , 2 libraries, 2 post offices, 12 shops, 7 pavilions [7].

In conclusion, it should be emphasized that a small homeland is of great importance for every person. By learning the history of our native land, we learn to honor the memory of our ancestors, understand the events of the past, and appreciate the culture and traditions of our people. The great Russian scientist Mikhail Vasilyevich Lomonosov wrote the following words: “A people that does not know its past has no future.” Indeed, without knowing the history of your country, city, village and family, you cannot be spiritually rich people and create a further chronicle of your Fatherland and native land.

List of used literature

- Abbasov A. Semiluki. History of the region / Abbasov A. - Voronezh: Central Black Earth Book Publishing House, 1994.

- Eletskikh V.L. Semiluki. Business card / V.L. Eletskikh, T.F. Pushkin. – Voronezh: Creative Association “Albom”, 2012.

- Krieger L.V. Seven bows on seven winds. On the Don shores / Krieger L.V. – Voronezh: Creative Association “Albom”, 2008.

- Prokhorov V.A. All Voronezh Land. / V.A. Prokhorov. – Voronezh: Central Black Earth Book Publishing House, 1973.

- History of the Voronezh diocese from its establishment to the 1960s. / Archbishop of Kherson and Odessa Sergius (Petrov). – Voronezh: Center for Spiritual Revival of the Black Earth Region, 2011.

- Bolkhovitinov E.A. Historical, geographical and economic description of the Voronezh province / E.A. Bolkhovitinov E.A. ; Scientific Red A.N. Akinshin; [Enter. article and notes by A.N. Akinshina]. – Voronezh: State Unitary Enterprise VO “Voronezh Regional Printing House”, 2011.

- Official website of the Semiluksky rural settlement administration: URL: http: //semiluk.ru (Date of access: 01/16/2017).

- Sdvizhkov I.Yu. Battles for Don crossings / I.Yu. Sdvizhkov // URL: https://www.vrn-histpage.ru (Date of access: 01/25/2017).

Author: A.V. Kruzhilov (cadet of the 21st training group of the Voronezh Institute of the State Fire Service of the Ministry of Emergency Situations of Russia)

Economy

The city has developed industry.

During Soviet times, the city established the production of fireproof products, building materials, household chemicals, etc.[21]. Among the largest enterprises in the city are a fireproof plant, a building materials plant, a food plant and a furniture facade factory. The now operating throughout the region was founded in Semiluki, which received press coverage as one of the examples of successful social entrepreneurship in Russia[22].

Semiluki

(Voronezh region)

OKATO code:

20249501

Founded:

1926

Urban settlement since:

1932

City since:

1954 City of district subordination (Semiluksky district, Voronezh region)

Center:

Semiluksky district

Telephone code (reference phone)

| 47372***** | — |

Deviation from Moscow time, hours:

0

Geographic latitude:

51°41′

Geographic longitude:

39°02′

Altitude above sea level, meters:

130 Sunrise and sunset times in the city of Semiluki

Transport

The Voronezh-Kursk railway passes through the city, there is a Semiluki stopping point, and there is a commuter service (three to four pairs of trains per day). Previously, long-distance trains Lipetsk-Belgorod, Voronezh-Belgorod, Voronezh-Kursk, and Kyiv-Voronezh had scheduled parking. Currently, all these trains have been canceled and the traffic rules at the checkpoint are Semiluki does not stop.

A highway passes through Semiluki, connecting the M-4 Don and A-144 Kursk-Saratov highways, bypassing Voronezh. The city is connected to the regional center by two road routes, and there is regular bus service.

City transport is represented by a network of minibus taxis.

Coat of arms of the city of Semiluki

Date of acceptance: 10/16/2008The coat of arms is registered in the State Heraldic Register of the Russian Federation under No. 4531.

State Register of the Russian Federation: No. 4531

Heraldic description:

“In an azure (blue, blue) field above a silver wavy tip there is a walled, with a stepped edge in accordance with the masonry, a scarlet (red) tip with an outer golden row of masonry.”

Coat of arms of the urban settlement of Semiluki in accordance with Article 19 of the Law of the Voronezh Region of July 5, 2005. No. 50-03 “On official and other symbols in the Voronezh region”, can be reproduced in two equally acceptable versions: - with the left free part - a quadrangle adjacent to the upper and left edge of the shield with figures of the coat of arms of the Voronezh region reproduced in it; - without the free part.

Rationale for symbolism:

The city of Semiluki is located in the northwestern part of the Voronezh region. With the construction of the Voronezh guard fortress in the 80s of the 16th century, the Semilukskaya land began to be intensively developed and populated. Already at the end of the 16th century, the following villages appeared: Semiluki, Endovishche, Gubarevo, and a little later - Devitsa, Stary Olshan, Medvezhye and others. The name Semiluki probably comes from the words “bend, curvature, bend, turn of the river.” The wavy extremity with seven bends reflects the name of the city and at the same time the Don River in the coat of arms, making the coat of arms vowel, which is a classic way of constructing a coat of arms. The city of Semiluki, the center of the Semiluki municipal district, arose in 1926 in connection with the start of construction of a refractory plant. The station on the Voronezh-Kursk railway line, and then the city, were named after the nearby ancient village of Semiluki. The edge lined with bricks symbolizes the leading enterprise of the region, OJSC Semiluksky Refractory Plant, one of the main products of which is brick of different brands, which is reflected in red and gold bricks. Gold in heraldry is a symbol of wealth, respect, intelligence, stability. Silver is a symbol of peace, mutual understanding, purity. Scarlet (red) color is a symbol of labor, courage, beauty, and celebration. Azure (blue, light blue) is a symbol of lofty aspirations, thinking, sincerity and virtue.

Author group: idea of the coat of arms: Dmitry Merkulov (Voronezh); heraldic revision: Konstantin Mochenov (Khimki), Yuri Korzhik (Voronezh); justification of symbolism and computer design: Yuri Korzhik (Voronezh).

Approved by the Decision of the Council of People's Deputies of the Semiluksky Municipal District dated October 16, 2008.

Sources: Union of Heraldists of Russia; Yu. Korzhik

VECTOR IMAGES:

»» Semiluki (Voronezh region), coat of arms

Attractions

The city has monuments to fallen soldiers during the Great Patriotic War: soldiers - aviators of the 2nd Air Army of the Voronezh Front (1978), fallen fire fighters and fallen workers of a construction materials plant[26], a memorial in memory of military personnel who died in peacetime . There is a monument to Lenin in the central square of the city. There are many memorial plaques in the city. In particular, memorial plaques were installed to the poet A.V. Koltsov, heroes of the Soviet Union N.D. Ryazantsev, I.M. Murza, A.E. Skvortsov, G.G. Telegin, heroes of the civil war T.A. Fitkalenko and N. A. Goncharov, participant in the storming of the Winter Palace A. A. Sorokin, director of the fireproof plant A. P. Stavorko, chief physician of the district hospital A. V. Goncharov, in memory of Operation “Trap”.

Semiluki, city, center of Semiluki district.

Located on the right bank of the Don River. A Slavic settlement of the 12th-13th centuries was explored near Semiluk in 1984-1988. The beginning of the city of Semiluki was laid by a railway siding that arose in 1894, named after a nearby village. The growth of Semiluk is associated with the construction of a refractory plant in 1926-1931.

The village at the plant was transformed into the workers' settlement of Semiluki in 1929.

From July 4, 1942 to January 26, 1943, the city of Semiluki was occupied by Nazi troops. There was a radio broadcasting station in Semiluki, the signals from which exploded mines in occupied Kharkov in November 1941. At the end of August 1943, the refractory plant resumed operation.

On November 18, 1954, the village of Semiluki was transformed into a city. In 1963, a household chemicals plant was built. In 1974, a mechanical and ceramic technical school was opened. In 1975, on the northern outskirts of Semiluk, a monument was erected on a mass grave; G.G. was present at the ceremony. Beregovoy, S.A. Krasovsky.

Since 1967, the city of Semiluki has maintained friendly relations with the Czech city of Jihlava.

Currently, in Semiluki there are JSC "Building Materials Plant", JSC "Agregat", LLC "Semiluki Pishevik", a technical and economic college, 2 secondary schools, 2 junior high schools, a sanatorium boarding school, a children's art school, a children's and youth sports school, Palace of Children's Creativity, station for young technicians, 2 libraries, 2 Houses of Culture.

Population: 21 600 (1989), 24 616 (2006), 26 505 (2014).

Natives of the city of Semiluk are A.M. Kulnev, A.V. Tkachev, lived A.V. Goncharov, I.M. Murza, V.M. Sidorov, I.I. Sokolov, A.E. Skvortsov, S.M. Sorokin, P.F. Shipilov, A.V. Marchukov.

On the southeastern outskirts of Semiluk there is the former dacha of I.S. Bashkirtsev, where A.V. visited Koltsov.

***

SEMILUKI, a city on the right bank of the Don, the center of the Semiluksky district.

Its emergence is associated with the construction of a large enterprise - a refractory plant - during the first five-year plan. The refractory clays found here were known back in the times of Peter the Great. Then they were used to make pottery. Before the revolution, clay mining began near the Latnaya station, where the workers' village of Latnaya later grew up. And the survey party came to the site of the city of Semiluki only in 1925. She chose a site for the construction of an enterprise and a future village. At that time, here, on the railway line, there was a stop with one small house, which was called after the neighboring village - Semiluki. In 1926, construction of the plant and village began. A tent city appeared near the station. At first, up to 600 people worked here, then the number of workers increased. The 1928 directory of populated areas indicates that there was one house at the Semiluki railway station. 4 people lived in it. During the construction of the plant (it was called a city plant) there were 4 houses in which 36 people lived. This meant permanent residents. In fact, the plant at that time was built by hundreds of people who lived in neighboring villages.

In 1929, the plant produced the first refractory. In 1932, the station village of Semiluki had 2,349 inhabitants. At the same time, it became a district center (before that, the district center was in the village of Endovishche). On November 18, 1954, the village of Semiluki, which at that time had about 10,000 inhabitants, was transformed into a city. Nowadays there are up to 15 thousand inhabitants (data from 1973 - note from the site authors). Here, in addition to the refractory plant, there are factories for sand-lime bricks, household chemicals, and a building materials plant. There is a branch of the Gubkinsky Mining College. The People's Museum of Local Lore has been opened. Two newspapers are published: the regional “For Communism” and.

The name of the city comes from the neighboring ancient village of Semiluki.

Excerpt characterizing Semiluki

- Go, eat something. Well, have a drink! – Dolokhov shouted to him from another room. - Don't want! – Anatole answered, still continuing to smile. - Go, Balaga has arrived. Anatole stood up and entered the dining room. Balaga was a well-known troika driver, who had known Dolokhov and Anatoly for six years and served them with his troikas. More than once, when Anatole’s regiment was stationed in Tver, he took him out of Tver in the evening, delivered him to Moscow by dawn, and took him away the next day at night. More than once he took Dolokhov away from pursuit, more than once he took them around the city with gypsies and ladies, as Balaga called them. More than once he crushed people and cab drivers around Moscow with their work, and his gentlemen, as he called them, always rescued him. He drove more than one horse under them. More than once he was beaten by them, more than once they plied him with champagne and Madeira, which he loved, and he knew more than one thing behind each of them that an ordinary person would have deserved Siberia long ago. In their revelry, they often invited Balaga, forced him to drink and dance with the gypsies, and more than one thousand of their money passed through his hands. Serving them, he risked both his life and his skin twenty times a year, and at their work he killed more horses than they overpaid him in money. But he loved them, loved this crazy ride, eighteen miles an hour, loved to overturn a cab driver and crush a pedestrian in Moscow, and fly at full gallop through the Moscow streets. He loved to hear behind him this wild cry of drunken voices: “Go! let's go!" whereas it was already impossible to drive faster; He loved to pull the man's neck painfully, who was already neither alive nor dead, avoiding him. "Real gentlemen!" he thought. Anatole and Dolokhov also loved Balaga for his riding skill and because he loved the same things as they did. Balaga dressed up with others, charged twenty-five rubles for a two-hour ride, and only occasionally went with others himself, but more often he sent his fellows. But with his masters, as he called them, he always traveled himself and never demanded anything for his work. Only having learned through the valets the time when there was money, he came every few months in the morning, sober and, bowing low, asked to help him out. The gentlemen always imprisoned him. “Release me, Father Fyodor Ivanovich or your Excellency,” he said. - He’s completely lost his mind, go to the fair, lend what you can. Both Anatol and Dolokhov, when they had money, gave him a thousand and two rubles. Balaga was fair-haired, with a red face and especially a red, thick neck, a squat, snub-nosed man, about twenty-seven, with sparkling small eyes and a small beard. He was dressed in a thin blue caftan lined with silk, over a sheepskin coat. He crossed himself at the front corner and approached Dolokhov, extending his black, small hand. - Fyodor Ivanovich! - he said, bowing. - Great, brother. - Well, here he is. “Hello, your Excellency,” he said to Anatoly as he entered and also extended his hand. “I’m telling you, Balaga,” said Anatole, putting his hands on his shoulders, “do you love me or not?” A? Now you've done your service... Which ones did you come to? A? “As the ambassador ordered, on your animals,” said Balaga. - Well, do you hear, Balaga! Kill all three and come at three o'clock. A? - How will you kill, what will we go on? - Balaga said, winking. - Well, I’ll break your face, don’t joke! – Anatole suddenly shouted, rolling his eyes. “Why joke,” the coachman said, chuckling. - Will I be sorry for my masters? As long as the horses can gallop, we will ride. - A! - said Anatole. - Well, sit down. - Well, sit down! - said Dolokhov. - I’ll wait, Fyodor Ivanovich. “Sit down, lie, drink,” said Anatole and poured him a large glass of Madeira. The coachman's eyes lit up at the wine. Refusing for the sake of decency, he drank and wiped himself with a red silk handkerchief that lay in his hat. - Well, when to go, Your Excellency? - Well... (Anatole looked at his watch) let’s go now. Look, Balaga. A? Will you be in time? - Yes, how about departure - will he be happy, otherwise why not be in time? - Balaga said. “They delivered it to Tver and arrived at seven o’clock.” You probably remember, Your Excellency. “You know, I went from Tver once for Christmas,” said Anatole with a smile of memory, turning to Makarin, who looked at Kuragin with all his eyes. – Do you believe, Makarka, that it was breathtaking how we flew. We drove into the convoy and jumped over two carts. A? - There were horses! - Balaga continued the story. “I then locked the young ones attached to the Kaurom,” he turned to Dolokhov, “so would you believe it, Fyodor Ivanovich, the animals flew 60 miles; I couldn’t hold it, my hands were numb, it was freezing. He threw down the reins, holding it, Your Excellency, himself, and fell into the sleigh. So it’s not like you can’t just drive it, you can’t keep it there. At three o'clock the devils reported. Only the left one died. Anatole left the room and a few minutes later returned in a fur coat belted with a silver belt and a sable hat, smartly placed on his side and suiting his handsome face very well. Looking in the mirror and in the same position that he took in front of the mirror, standing in front of Dolokhov, he took a glass of wine. “Well, Fedya, goodbye, thank you for everything, goodbye,” said Anatole. “Well, comrades, friends... he thought about... - my youth... goodbye,” he turned to Makarin and the others. Despite the fact that they were all traveling with him, Anatole apparently wanted to make something touching and solemn out of this address to his comrades. He spoke in a slow, loud voice and with his chest out, he swayed with one leg. - Everyone take glasses; and you, Balaga. Well, comrades, friends of my youth, we had a blast, we lived, we had a blast. A? Now, when will we meet? I'll go abroad. Long lived, goodbye guys. For health! Hurray!.. - he said, drank his glass and slammed it on the ground. “Be healthy,” said Balaga, also drinking his glass and wiping himself with a handkerchief. Makarin hugged Anatole with tears in his eyes. “Eh, prince, how sad I am to part with you,” he said. - Go, go! - Anatole shouted. Balaga was about to leave the room. “No, stop,” said Anatole. - Close the doors, I need to sit down. Like this. “They closed the doors and everyone sat down. - Well, now march, guys! - Anatole said standing up. The footman Joseph handed Anatoly a bag and a saber, and everyone went out into the hall. -Where is the fur coat? - said Dolokhov. - Hey, Ignatka! Go to Matryona Matveevna, ask for a fur coat, a sable cloak. “I heard how they were taking away,” Dolokhov said with a wink. - After all, she will jump out neither alive nor dead, in what she was sitting at home; you hesitate a little, there are tears, and dad, and mom, and now she’s cold and back - and you immediately take him into a fur coat and carry him into the sleigh. The footman brought a woman's fox cloak. - Fool, I told you sable. Hey, Matryoshka, sable! – he shouted so that his voice was heard far across the rooms. A beautiful, thin and pale gypsy woman, with shiny black eyes and black, curly, bluish-tinged hair, in a red shawl, ran out with a sable cloak on her arm. “Well, I’m not sorry, you take it,” she said, apparently timid in front of her master and regretting the cloak. Dolokhov, without answering her, took the fur coat, threw it on Matryosha and wrapped her up. “That’s it,” said Dolokhov. “And then like this,” he said, and lifted the collar near her head, leaving it only slightly open in front of her face. - Then like this, see? - and he moved Anatole’s head to the hole left by the collar, from which Matryosha’s brilliant smile could be seen. “Well, goodbye, Matryosha,” said Anatole, kissing her. - Eh, my revelry is over here! Bow to Steshka. Well, goodbye! Goodbye, Matryosha; wish me happiness. “Well, God grant you, prince, great happiness,” said Matryosha, with her gypsy accent. There were two troikas standing at the porch, two young coachmen were holding them. Balaga sat down on the front three, and, raising his elbows high, slowly took apart the reins. Anatol and Dolokhov sat down with him. Makarin, Khvostikov and the footman sat in the other three. - Are you ready, or what? – asked Balaga. - Let go! - he shouted, wrapping the reins around his hands, and the troika rushed down Nikitsky Boulevard. - Whoa! Come on, hey!... Whoa, - you could only hear the cry of Balaga and the young man sitting on the box. On Arbat Square, the troika hit a carriage, something crackled, a scream was heard, and the troika flew down Arbat. Having given two ends along Podnovinsky, Balaga began to hold back and, returning back, stopped the horses at the intersection of Staraya Konyushennaya. The good fellow jumped down to hold the horses' bridles, Anatol and Dolokhov walked along the sidewalk. Approaching the gate, Dolokhov whistled. The whistle responded to him and after that the maid ran out. “Go into the yard, otherwise it’s obvious he’ll come out now,” she said. Dolokhov remained at the gate. Anatole followed the maid into the yard, turned the corner and ran onto the porch. Gavrilo, Marya Dmitrievna’s huge traveling footman, met Anatoly. “Please see the lady,” the footman said in a deep voice, blocking the way from the door. - Which lady? Who are you? – Anatole asked in a breathless whisper. - Please, I've been ordered to bring him. - Kuragin! back,” Dolokhov shouted. - Treason! Back! Dolokhov, at the gate where he stopped, was struggling with the janitor, who was trying to lock the gate behind Anatoly as he entered. Dolokhov, with his last effort, pushed the janitor away and, grabbing the hand of Anatoly as he ran out, pulled him out the gate and ran with him back to the troika. Marya Dmitrievna, finding a tearful Sonya in the corridor, forced her to confess everything. Having intercepted Natasha’s note and read it, Marya Dmitrievna, with the note in her hand, went up to Natasha. “Bastard, shameless,” she told her. - I don’t want to hear anything! - Pushing away Natasha, who was looking at her with surprised but dry eyes, she locked it and ordered the janitor to let through the gate those people who would come that evening, but not to let them out, and ordered the footman to bring these people to her, sat down in the living room, waiting kidnappers.